When Dambudzo Marechera Met Aaron Chiundura Moyo – A Brief History of Zimbabwe’s Language Wars

In newly independent Zimbabwe, language wars erupted between homecoming writers who had made their names in the language of exile and writers who had worked with the state-run Literature Bureau to grow a Ndebele and Shona canon. Onai Mushava revisits the cold encounters of two of Zimbabwe’s best known writers, Dambudzo Marechera and Aaron Chiundura Moyo, in conversation with their contemporaries and critics.

Dambudzo Marechera’s moods switched between extremes like an Eskimo in Hades. Everyone around him was the shadow of a conspiracy to be resisted with unpredictable outbursts. Sometimes his big ideas had to be personalized against an immediate target; sometimes he was the drunken master with his unconscious in the open. Aaron Chiundura Moyo, the renaissance man with a neat afro, cross belts and a hunky smile, politely brushed disses aside and gave nothing away. Yet both men could not feel at home during the writers’ workshops of the early 1980s.

Newly home from exile, Marechera never stuttered about being Zimbabwe’s best writer. Except that his manuscripts were hardly making it past the editors. Some of these editors were Mambo Press’ Chenjerai Hove, ZPH’s Charles Mungoshi and College Press’ Stanley Nyamfukudza. They felt that Marechera was not communicating with “the people”; he was certain that the “village writers” were spiking him to protect their own turf. Workshop organizer Nyamfukudza came around to publishing Mindblast not long before the 1984 book fair, but Marechera remembered him as the state agent who had helped writer-politician Edison Zvobgo to strongarm him away from the 1983 book fair.

Moyo had more modest reasons for feeling left out. The Ziva Kwawakabva writer had found his way from a hard childhood at Shoeshine Farm and yard jobs in the city to the center of the arts scene along with his brothers sungura pioneer Jonah Moyo and mbira-guitar pioneer Joshua Dube. But, in the early 1980s, homecoming scholars and writers in English, sidelined during the Rhodesian Literature Bureau era, had taken over the Harare scene. Moyo felt some type of way among them for not having finished school and broke this lettered company’s English-only code with his Shona presentations.

“Take him out; he is not a writer! Munyori, not an author,” was the first time Marechera played an Honorable Madisa on Moyo. Although Musaemura Zimunya remembers Marechera holding no permanent grudges and never repeating an insult, Chiundura was not so lucky. After the workshop, the two writers would reunite to co-present a seminar at a school in Highfield, Harare.

“Uyu Aaron munyori; he is not a writer,” was the introduction Moyo got from the writing friend he had bought a cab ticket and chikari (traditional beer) for on the way. Marechera made good on the distinction between writer and munyori by denying Moyo the stage till the day was almost over. Students walked out on Moyo’s belated presentation as English-language writers also used to, back at the workshops.

Aaron Chiundura Moyo (right) with his brother and sungura music legend Jonah Moyo (Courtesy: A.C Moyo)

College Writer, Village Storyteller

The literary divide of the early 1980s provided for drama of this sort, Zimunya recalled, though he had no recollection of the workshop incident. Most of those writing in English had been literature students in high school and university, therefore intimate with theory and confident in expressing themselves, he explained, while Shona writers relied on their own initiative and natural talent. Moyo was such a self-taught writer, having failed to go beyond junior certificate.

“Particular immersion in English could spawn attitudes of pride, arrogance and superciliousness – or the impression of such, depending on the occasion or audience. And Dambudzo, ever the well-rehearsed and articulate posier, was never one to miss the opportunity to impose himself on his audience,” Zimunya said, adding that those less familiar with Marechera’s wilding would forever find him insulting and repulsive.

Marechera was a man of ideas and a child of crisis. Ideas in time of crisis are not merely expressed but embodied; politics is not just your conviction but your condition. Marechera was negatively conditioned by the rootlessness, violence and repression of the colonial township. If he sounded extreme in his views on fellow writers – this is the dude who once said Charles Mungoshi is not an artist and was disappointed with Wilson Katiyo and Zimunya for double-crossing their writing with day jobs – he probably saw in them faces to pin to his ideas. In Moyo, he found an immediate target for his well-documented resentment for Shona novels.

In newly independent Zimbabwe, language wars erupted between homecoming writers who had made their names in the language of exile and writers who had worked with the state-run Literature Bureau to grow a Ndebele and Shona canon. Onai Mushava revisits the cold encounters of two of Zimbabwe’s best known writers, Dambudzo Marechera and Aaron Chiundura Moyo, in conversation with their contemporaries and critics.

“Somehow, they kept on inviting me though all my addresses were in Shona to the disappointment of many in attendance. Some walked away as soon as I stood to speak,” Moyo recalled. “When asked to use the ‘correct language’, I would passionately stand my ground and say ‘No!’ Chenjerai Hove and Stephen Chifunyise did not like this bad habit of speaking in a local language but Musaemura Zimunya seemed to enjoy it in a way,” he said.

Writers’ platforms of the time were not made for writers like Moyo. “Following the birth of the Zimbabwe International Book Fair (ZIBF) and Zimbabwe Writers Association (ZIWU), whose chosen language of communication was English, indigenous languages writers were further marginalized from the perceived center of literary culture and glamour,” Zimunya explained.

“The majority of ZIWU’s membership wrote in English, even though we had Giles Kuimba in the executive structure. Thus the literary divide was to widen even further. At the time neither ZIBF nor ZIWU made any deliberate effort to reach out to the indigenous languages writing community, a development which led to the formation of the Zimbabwe African Languages Writers Association by the aggrieved authors,” Zimunya added.

While some writers of “status” feigned hospitality, “Dambudzo Marechera did not hide his dislike of me and disqualified me as an author twice,” Moyo recalled. The first time Moyo attracted the munyori interjection, he had made a contribution in Shona.

Bad Boy Strikes Again

There was no question about going to toe-to-toe with Marechera, a bad boy and cult hero worshipped by fellow writers. Moyo took comfort in that few people had heard the interjection and let it pass. He would soon catch the Marechera show again at a book event officiated by President Canaan Banana at Kingston’s Bookshop. The literary community was already packed inside the venue when a not-so-sober Marechera showed up, making funny remarks that shifted the attention to him.

“His readers followed him to the bookshelves. I was busy looking at new publications on the Shona Section and pretended not to have noticed him. He went to the English Section with all eyes on him and would pick a book, take a look, put it back and so on. We did not know that he was, in fact, looking for his new book, Mindblast, but somehow couldn’t locate it,” said Moyo.

A restless Marechera addressed himself to the seated delegates at the top of his voice: “My new book has been banned! Look they have banned my book!” He had already tasted this ordeal when his second novel, Black Sunlight, got banned for “obscenity and blasphemy” while he was still in UK. “I couldn’t ignore him because I wanted to read the new ‘banned’ book,” said Moyo.

A Second Undressing

Next time fate brought Moyo his way, Marechera would undress him in front of high school students. This was the doing of their mutual former student, one Makahamadze who had frequented Moyo’s place for writing lessons as a Form 4 student before going on to study literature in Mr Marechera’s A Level class at Ranch House College.

By the 1984 book fair, Makahamadze himself had become a teacher at a Highfield school. He invited Moyo to address students as they had one of his novels on the syllabus. “He advised me that I was going to share the stage with Marechera and I liked it very much because I wanted to show Dambudzo that a munyori was equal to a writer in front of students.”

Makahamadze was to meet his two former teachers on corner Kenneth Kaunda and Julius Nyerere and travel with them to Machipisa. He, however, excused himself to go ahead and take care of school business, leaving Moyo to wait for Marechera. The Mindblast dude arrived, unusually dressed in a suit and coldly nodded to Moyo’s greetings.

“Where is the car to take me to the school?” Marechera asked.

Moyo said no car had been arranged. They had to catch a Peugeot 404.

“Who is going to pay?” Marechera asked.

“I will,” Moyo answered.

Moyo jumped into the back of a cab whose seats were already packed, mindful of commencing time.

“Comrade, munosara (you will be left behind)!” he shouted at Marechera.

Cde Dambudzo jumped in and they shared the boot of the 404 to Machipisa in silence.

Marechera was thirsty on arrival. They quibbled over the time they were expected at the school and Moyo agreed with Marechera that they still had minutes to kill. They entered a bar near Gwanzura Ground where teetotalist Moyo bought Marechera two jugs of chikari as he had no money for clearer beer. Marechera downed his beer in silence while Moyo resented his friend’s coldness and lack of “Fadza Mutengi” (please-the-buyer) ethic.

The two celebrities had expected a rousing welcome but the school was bent to routine and their young host was nowhere in sight. Makahamadze was, in fact, frantically negotiating with other teachers to release students for his seminar. Marechera saved himself the awkward spectacle by disappearing into the classroom of a former classmate. A teacher who liked Moyo’s novels called him into his own classroom and asked how such big writers had been fooled by a temporary teacher who was new at the school.

But it was not hard for the teachers to quickly gather a star-struck audience for the writers. Marechera went over to ask Moyo how much money he had been given. “Nothing,” the television guy said, and Marechera shouted that he wanted his money.

Meanwhile, Marechera’s teacher friend had managed to administer some order.

Dambudzo read the blurb of Moyo’s book as the audience waited for him to speak first. He threw back the copy to the girl who had been holding it and told the seminar: “Uyu Aaron munyori; he is not a writer.”

The students roared wild at the diss and enjoyed Marechera’s uncensored presentation as it went on forever till the school day was almost up. As soon as Marechera finished, most students trooped out, leaving munyori Aaron to address himself.

“I walked to Kambuzuma because I had spent the little I had on Dambudzo. He disappeared with his friend. From that day, I watched him from a distance and he never bothered about me either,” Moyo said.

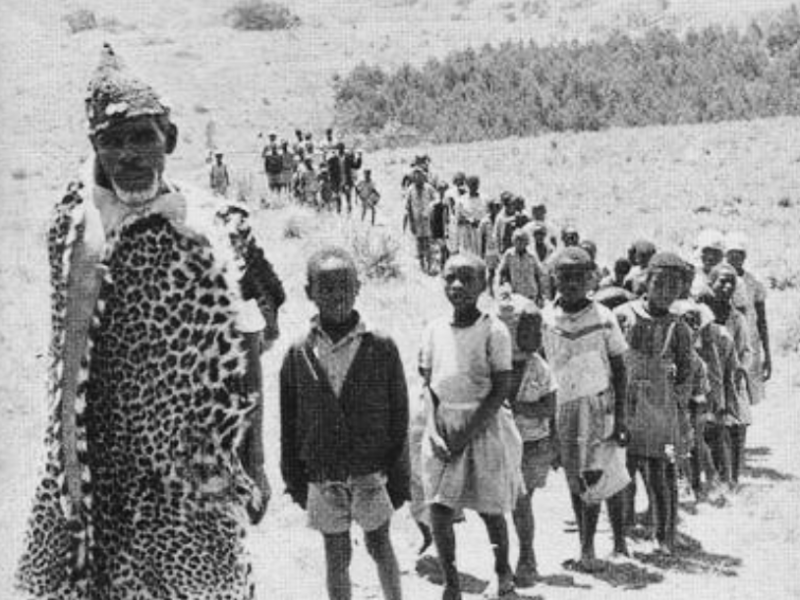

(From left to right) Aaron Chiundura Moyo, Shimmer Chinodya, T.K Tsodzo, Ignatius Mabasa and Memory Chirere at the 2013 launch of Mabasa’s novel, “Imbwa yeMunhu” (Picture Credit: Tinashe Muchuri)

Marechera Cared Nothing for a Literature Bureau

Marechera’s ungenerous opinion of Moyo, one of the most foremost Shona novelists of all time, was an extension of his resentment for the Literature Bureau, the government department which was facilitating the publication of Ndebele and Shona novels. Incepted in the decade of Marechera and Moyo’s birth, the department would have been responsible for much of the literaure the two artists grew up on, at least in school. The Literature Bureau has a conflicted legacy, praised by some for setting off an indigenous languages renaissance and reviled by others as an arm of Rhodesian censorship which limited the literature of the era to safe, “native” themes.

“Since the late 1950s, Zimbabwean literature was dominated by indigenous language writers such as Bernard Chidzero, John Marangwanda, Solomon Mutswairo, Patrick Chakaipa, Paul Chidyausiku, Giles Kuimba, Thompson Tsodzo and, soon, Charles Mungoshi in Shona and Ndabaningi Sithole, G.N.S. Khumalo, S. Mahlangu, Ndabezinhle Sigogo, Mayford Sibanda and later Mthandazo Ngwenya in isiNdebele. Without any shadow of doubt, these authors were the true pioneers of the literary history of the African people in Zimbabwe,” Zimunya said.

“However, there were other writers who were plying their trade in English such as Stanlake Samkange, Ndabaningi Sithole, Lawrence Vambe, Gibson Mandishona, Edison Zvobgo, Henry Pote and Samuel Chimsoro who can lay claim to the title of ‘founding fathers’. Others like Charles Mungoshi, Mthandazo Ngwenya, Aaron Chiundura Moyo, Dambudzo Marechera, Wilson Katiyo and Musaemura Zimunya can be viewed as the immediate heirs to the founding fathers,” he explained.

Marechera’s position on the bureau and the “founding fathers” was decidedly parricidal. “After UDI (Unilateral Declaration of Independence) in 1965 Ian Smith deliberately created the Rhodesia Literature Bureau to promote a certain kind of Shona and Ndebele literature that would be used in the schools and perpetuate the idea that racism is for the good of the blacks,” Marechera said in one interview. As a matter of fact, the bureau had been established few years before UDI.

“And we had writers who were writing the very books Smith wanted the blacks to read. In primary school I was taught Shona literature that caricatures black people and which was in line with the specific political policies before independence. One of the main themes in Shona literature of that period was the story about a person coming from the rural areas thinking that he’d have a good life in the city. Then he or she comes to the city and goes through hardship and decides to go back to the rural areas because that’s where heaven is.

“Now this was in direct line with the urban-influx control policy. Blacks were being discouraged by the city council and by the government to come to the cities. In other words, even before I left the country, the literature that was being written here had no relevance to me or even to our people, to those who knew. Before independence you had two schools of thought among writers: those who participated in Smith’s propaganda programme, and those who had to run into exile and write protest literature. You will find that after independence the ones who were in the first school are now the ones in high positions, and those who were part of the Zimbabwean protest literature are the ones who are having problems or who have been forced to compromise themselves,” Marechera said, perhaps explaining his coldness to Moyo who was already popularly juggling literature and television at the time of their encounters while Marechera’s experiments could not make it into the curriculum or even the printing press to begin with.

His fellow Guardian Fiction Prize winner, Petina Gappah, picks up Marechera’s distaste of the Literature Bureau and Shona books in her 2019 play, Black Sunlight. “Good lord. The Literature Bureau! They are not still churning out their drivel are they? Don’t tell me you are still writing that juvenilia, all those Shona poems? You really should write in English. It’s the only way to get anywhere,” Gappah’s Marechera character says on reunion with a writer-friend from high school.

“The best thing about being out of the country is that I haven’t had to see any of this stuff. I haven’t read Shona since school, since our Standard 6 texts, Kutonhodzwa kwaChauruka and Ta-ta-tambaoga Mwanangu. I offended the teacher, do you remember, Mr Churu… by saying the authors had copied Shakespeare. It’s true! One is just a poor man’s Hamlet and the other a poor man’s Macbeth.

“How much can you possibly have to say in such a provincial language? Do you know there are only five named colours in Shona? I mean tsvuku, is red, right. But there are reds and there are reds. There’s crimson, maroon, scarlet, cherry.”

The observation by Gappah’s Marechera cuts in both directions. To paraphrase a passage from The Black Insider, the writer expands or subverts his language as he encounters its poverty, possibilities or power games in the process of writing. Shona has been most obviously growing (some elders say shrinking) lately through Zimdancehall and social media. Activity in the other disciplines, say an idiosyncratic Tinashe Muchuri or Ignatius Mabasa novel, equally expands the dictionary. For all its Rhodesian baggage, the Literature Bureau opened the space for a cultural record.

Lost at Sea

The House of Hunger author was hopelessly lost at sea on this front, said Robert Muponde. “Marechera himself was not sufficiently literate where Shona Literature is concerned, hence he made very narrow and derogatory remarks about its contents,” Muponde argued, breaking with conventional criticism of the Literature Bureau.

Muponde has previously taken on critics who believed that Marechera wrote explicit love poetry that would not have seen the light of day in Shona. Such a position presupposes the parish purity of Shona versus Marecheran subversion. “I demonstrate the existence of very explicit traditional Shona love and sex poetry found in madanha emugudza. These poems are an ordinary performance and occurence among the Shona, but context-bound. So the ignorant critical exuberance resulted in Marechera’s cultural and political bluff not being called while he was still walking the streets of Harare,” Muponde said.

“However, he is not alone in trying to create binary divisions between Shona and English. He is joined by Emmanuel Chiwome who saw the lack of political themes and protest and in pre-1980 Shona literature as an indication of its kwashiorkor. That is really a bald view, given that protest and politics do not reside in the discourse of the armed struggle only!” Muponde’s view particularly fits one-dimensional Zwitterati’s recent panning of Zimbabwean musicians for “having no politics.”

Moyo’s example of Patrick Chakaipa’s Garandichauya as a critique of hurungu (acquired Englishness) is an extension of the view that the cultural is political. Of course, this would be the sort of novel Marechera would be happy to pan for aiding Rhodesian propaganda.

Chirere notes “the veiled suggestion” in Garandichauya that “black people should stay in the Tribal Trust Lands if they are to make any real meaning with their lives.” For music connoisseur and feminist Joyce Jenje-Makwenda, this is the logic at work in the old music hit, “Kudendere”. In her 2013 book, Jenje-Makwenda agrees the Harare Mambos Band queen, Virginia Sillah Jangano, that the early pop classic romanticizes the village in order to make city life unavailable to women.

But there is something to redeem from Moyo’s argument. The city was, after all, as much of a construction of Rhodesian production as the reserve. The 19th century Romantic School is considered subversive for imagining organic spaces in the countryside and in classic Europe, away from the rot and rote of Industrial London. Why should early Shona novelists be panned for a similar operation? Whatever one makes of this, Father Chakaipa’s romances are most probably the “missionary chickenshit” Marechera had in mind when he demanded: “Who wants us to keep writing in ShitShona and ShitNdebele languages… who else but the imperialists?”

Cold War 1 & 2

Muponde identified two more “false” divides between home writers and diaspora writers, questioning “the critics who buy into the divide between those who remained in Rhodesia and wrote there and those who left the country and wrote out there. This narrow view is captured in Kizito Muchemwa’s famous introduction to Zimbabwean Poetry in English. It has consequently been adopted and given sustenance by the post-2000 dispensation, which creates false binaries between Zimbabweans in the diaspora and those who remained behind.”

Perceived divides went so far as to shape academic culture. “For a long time during the eighties, the African Languages Department and the English Department at the University of Zimbabwe played out this simmering intellectual tension and cold war. One would not be wrong to suggest that there was a hereditary feeling of inferiority and superiority among both staff and students of these departments, genuine or perceived,” said Musaemura Zimunya.

While censorship applied across language, Moyo thinks different options were available to writers in the two languages. “To me, it wasn’t a question of a particular language when it came to novel writing. Writers were just not allowed to touch on political themes in whatever language.

“Those who wrote in English had their works banned yet a writer writes to be read. Now, if such a work was in English, the book could find wider readership outside Rhodesia unlike Shona,” argued Moyo. “Remember what happened to Feso? Maybe those people complaining about the old Shona novel’s lack of political themes are indirectly suggesting the writers should not have put pen to paper until Rhodesia became Zimbabwe.”

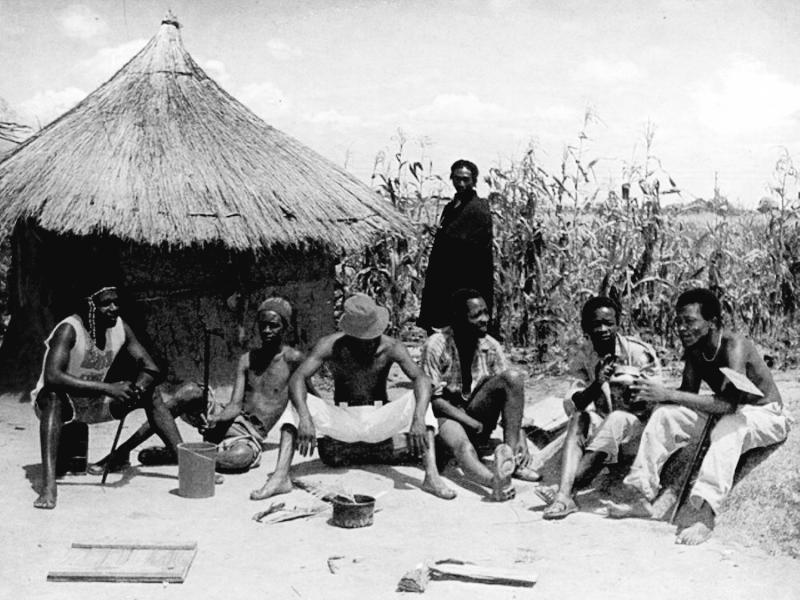

Aaron Chiundura Moyo, Musaemura Zimunya, T.K Tsodzo and Maunganidze Gomo at the 2015 Zimbabwe International Book Fair (ZIBF) Indaba (Picture Credit: Beavan Tapureta)

What if Marechera Is a Munyori Too?

If Marechera is infamously not an African writer, can he be reread as a Shona writer instead? (In asking this question one is cautious not to slip into unnecessary binaries between Shona and other Zimbabwean languages as these are, after all, promiscuous neighbors.) Is Marechera fully exorcised of Shona, the ghetto daemon he tried to escape from, into English literature? Maybe his Shona is a found object not a received wisdom, a ghost of his postmodern parricide without the romance and essence it is allowed by older novelists?

Marechera’s umbilical cord refuses to blend into the soil, escaping as the snake that bruises the ancestors’ heels. But if Marechera redeems stories and myths and pisses on confessional wisdom, if he is the trickster, the jester, the wit and the vulgarian rather than the messenger or the courtier, is the Shona or Bantu folk space not broad enough to have birthed, or at least accommodated, him?

The ancients already have a saying that he who inserts proverbs gets what he wants, admitting that two proverbs can be mutually opposed so that wisdom is neither fixed nor infallible. Tradition has a place for the nephew who corrects the elders, the village fool who confuses the wise and the poet who “flatters” the king to shame.

“If you read House of Hunger carefully, minus the strong language, you will discover a lot of old Shona novel-writing,” Moyo points out. When one considers Muponde’s suggestion, the strong language, in fact, makes Marechera the more ancient poet. A.C Hodza catalogues some of these NSFW old poems and songs for Flora Veit-Wild’s Writing Madness.

Chirere identifies two use cases for Shona by Marechera, the “repackaged expression of a very well-known Shona story, ‘Vana varasika musango’” in The House of Hunger and the literal Shona play, “Servants’ Ball”, in Scrapiron Blues. There is hardly a Marechera equivalent of Chenjerai Hove’s “Shona novels in English.” Perhaps, the confessional demands of such an operation explain why Marechera called Chinua Achebe a “village writer.”

Criticism and Conspiracy

More confusing than Marechera’s ideas is the level at which to take his games seriously. Veit-Wild complains in the Sourcebook about Dambudzo’s postmodern habit of giving mutually contradictory details about his life. Calling Marechera the actor, the paranoid, the postmodernist, the alcoholic or the obscurantist are classic sidesteps from having to deal with his questions and ideas. But playing down these aspects of his complex persona is a boring exercise in reverse respectability and political correctness.

Zimunya provided a career context for Moyo’s encounters with the difficult Gemini. “All Marechera would have needed was for Chiundura Moyo to introduce himself or for someone to introduce him for Dambudzo to stick it into him. Easily. Why? Because when Dambudzo arrived back home in February 1983, he found that there were writers already who were more famous locally than him – which riled him no end. Thus, he went about doing anything to prove that he was the genuine article and that all the other writers were “village writers” – a term he would use against Chinua Achebe and Ama Ata Aidoo.”

While Marechera did not nurse his beefs, according to Zimunya, getting spiked by fellow writers led him to a conspiracy theory to this effect: “How can I get published in a country where every company has employed one of my rivals?”

Featured image © Ernst Schade.

Leave a Reply