More Dambudzo Marechera Letters – To Karen, Flora, Amelia and Samantha (Part 1)

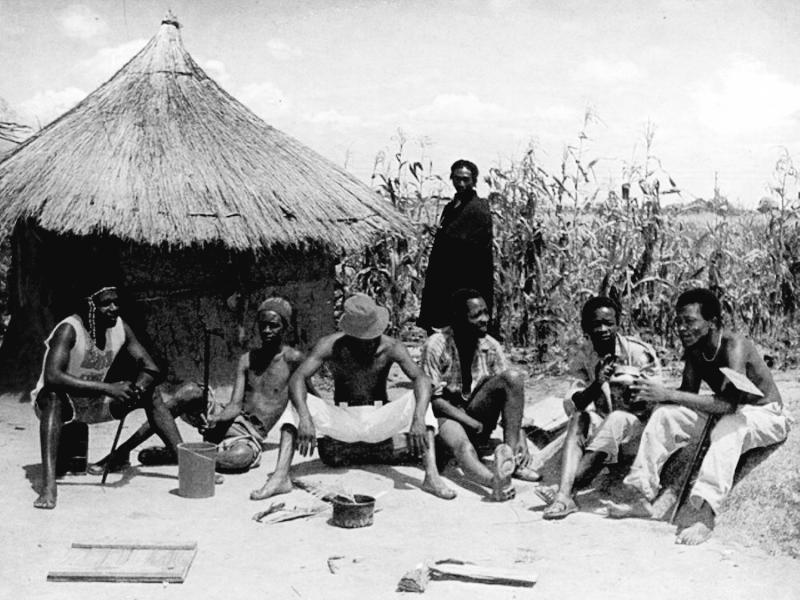

Dambudzo’s boyhood in the slums formed in him the parallels of black decay and white paradise. From here, he is one step away from extending the parallels to language, love and literature. His comment, “I actually find love among people of the same race as incest,” may be taken to idealise White love and White culture as a field of becoming. He shares his crude environment with Black women just trying to survive violence and prostitution but finds his spiritual fit among White artsy types, Patricia in The House of Hunger, Blanche et al in Black Sunlight, Olga in Mindblast, Barbara, Liz and Helen in The Black Insider.

Dambudzo Marechera wrote about rough and rowdy days on the edge of town. His stories of violence, grim survival and soul hunger in Rusape, London, Cardiff and Harare emphasise street cred over love. And yet, a lot of what has been written about Marechera comes back to the cheesy old theme. His stated preference for White girlfriends has been brought up by critics who accuse him of misogyny towards Black women and disconnect from the African image. His kept women, Immaculate in The House of Hunger and Marie in Black Sunlight, disprove critics’ reduction of his female characters to Black prostitutes and White peers. But their names alone caricature female vulnerability in macho dystopias that forbid their existence. Marechera had failed to picture his mother, the primary image of femininity, outside Rhodesian violence and prostitution. He immaculately conceives the figures of Immaculate, Marie and Grace to tease his mother complex.

Dambudzo’s boyhood in the slums formed in him the parallels of black decay and white paradise. From here, he is one step away from extending the parallels to language, love and literature. His comment, “I actually find love among people of the same race as incest,” may be taken to idealise White love and White culture as a field of becoming. He shares his crude environment with Black women just trying to survive violence and prostitution but finds his spiritual fit among White artsy types, Patricia in The House of Hunger, Blanche et al in Black Sunlight, Olga in Mindblast, Barbara, Liz and Helen in The Black Insider.

Bright stars of the Black middle class like Zimbabwean writer Petina Gappah have expressed an understandable distance from Marechera. But Dambudzo has also travelled the upper reaches of Blackness to discover himself in female culture snobs. As artists rather than muses, Grace and Tsitsi give off more agency than projection. With names out of the same Bible pages as Immaculate and Marie, Dambudzo has favoured them to survive the shocking appetites of Bohemia.

Black skinhead, White muses

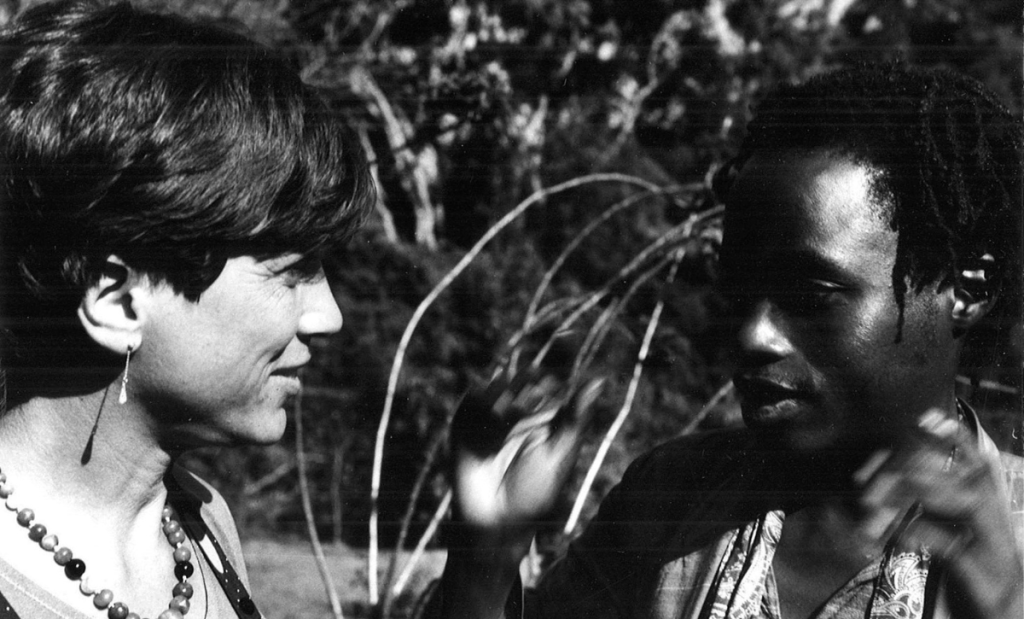

Much of what Dambudzo’s German biographer, Flora Veit-Wild, remembers about him is tinged with their romantic involvement. In recent years, “Dambudzo Marechera’s letter to his white girlfriend” has been a viral hit on the internet, never mind the fact that the letter was only written in 2011, some 24 years after Dambudzo’s death in 1987. Zambian writer Austin Kaluba disappears into Marechera’s voice in his “Samantha letter”, complicating Dambudzo’s low opinion of white Salisbury, Oxford and London with his love for white women. In the course of documenting Marechera’s free thought project, two-time biographer David Caute gives a contested account of Marechera as a white woman’s gigolo. But what did Dambudzo himself have to say about his White lovers?

Since Frantz Fanon psychoanalysed sex across the colour bar in Black Skin, White Masks, interest in the matter has stayed undefeated

Since Frantz Fanon psychoanalysed sex across the colour bar in Black Skin, White Masks, interest in the matter has stayed undefeated. On his latest album, Mr. Morale and the Big Steppers, Kendrick Lamar’s first time with a White girl is payback for her uncle (Sam, I presume?)’s use of the prison system to lord it over black bodies. In Alain Mabanckou’s Black Bazaar, the Congolese narrator is mocked for coming all the way to France just to wind up with a homegirl disapprovingly named Original Color. Mabanckou’s drinking mates refuse to bless his newborn daughter because the little one is a missed opportunity to make France pay the colonial debt. Marechera is more committed to ancestral score-settling than Mabanckou. “And even when I am making love to her,” he says of Amelia, his Cemetery of Mind muse, “I find that I am actually with my whole self trying to fool myself that I am avenging myself against the whole white race.”

Karen

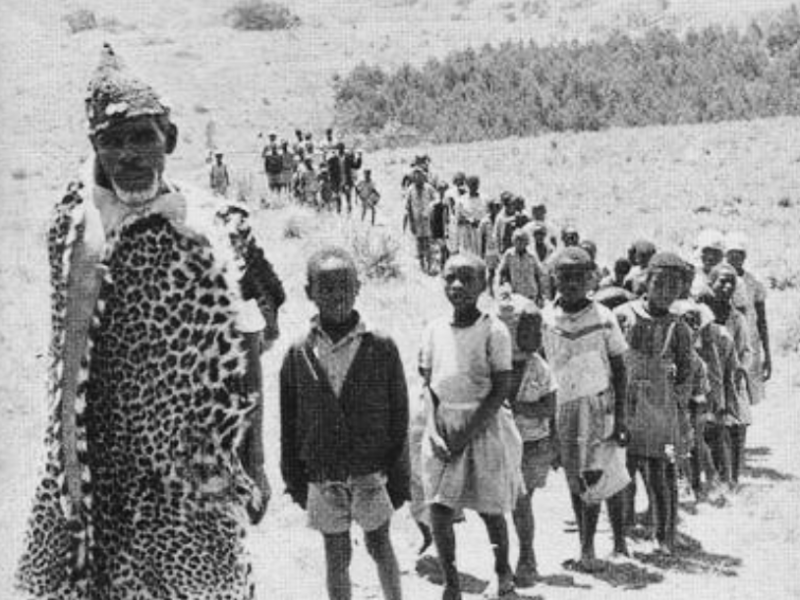

During the Mindblast book cycle,his first major work to be written in Zimbabwe, Marechera enjoyed the comforts of a Mutoko-based German expat teacher. Karen, named Olga for the purposes of the book, is a strong real-life presence in the Harare journal of the 1984 book. When Dambudzo is not writing in Cecil Square, now Robert Mugabe Square, sleeping on the streets, or killing time in a pub, he carries on a night of passion in Karen’s weekend hotel.

The lovers talk about their hard-drug experiences, childhood complexes, nostalgia for hippy sixties and seventies and low opinion of patriotic projects, the latest of which is afoot in newly independent Zimbabwe. Karen is down with the cruel detonation of Zimbabwe’s socialist and nationalist project project that is Dambudzo’s Mindblast. She washes the writer-tramp’s clothes, buys him food, reads his new Mindblast pages and answers his pathological soul hunger for a motherly pat on the shoulder. Only, these melodramatic reconstructions of Bob Dylan’s “When I Paint My Masterpiece” are too good to last. On Sunday morning, Karen will leave Harare for work, abandoning Dambudzo to the streets and to madness.

In the weekend restaurant, a newly returned Karen tells starving and unwashed Dambudzo to eat up. “After you eat then go to our hotel room and sleep. Just rest. Or type. Whatever you want to do. And then afterwards let’s go for a drink, and let’s go and dance,” Marechera remembers Karen to Dutch journalist Alle Lansu. The human touch she embodies for Dambudzo so overwhelms him that whenever he reads back to their dates in Mindblast, he goes out to drown the feeling with a strong beer.

“I was having a normal life by instalments,” says Marechera. “Because each Sunday morning we would wake up and I would know that, well, she is going back to school teach and I am now going back into the streets to survive. That’s why that journal section is very important to me. For me it was good to know that there was someone who cared. But it was, yeah, it was… In other words, I don’t know.”

Chenjerai Hove Photo: Wiki commons/Perijove

There is not much else written about Karen. Chenjerai Hove talks about a Marechera girlfriend who was a German expat teacher, in an unpublished conversation with a fellow Zimbabwean writer. The last time Hove heard of her in 1995, she was in Masvingo, fighting Aids-related complications.

Hove also recalls the expat teacher and Flora Veit-Wild being chased by Dambudzo’s relatives from his funeral in 1987. His recollections have not been independently verified, and it’s not clear whether the Mutoko teacher is the one who had since moved to Masvingo.

Placing full-time writing over a day job, industry performatives, a social safety net and the thirty pieces of silver usually reserved for State House intellectuals, the committed writer always already got one foot in the Bohemian black hole. But Bohemianism, as Marechera sees it, is the side outcome rather than the gameplan. “Bohemianism is not a lifestyle for the serious writer,” he explains in Mindblast. “It is dictated by harsh poverty which is dictated by the fact that full-time writing brings in little or no return in the early stages of one’s career.”

Flora Veit-Wild Photo credit: @VeitFlora via Twitter.

Whatever Dambudzo makes of it, Marechera mythology is decisively fixed around his Bohemian persona. The cult of Marechera, recruited from each new generation since the 1980s, involves the Bohemian rites of growing out your hair, drinking yourself stupid, shitting on a nine-to-five, opting out of Zimbabwe’s tired slogans and, why not, chatting up a white lover-patron Rastaman-style.

Flora

I have not yet read Flora Veit-Wild’s 2020 biography, They Called You Dambudzo. There would be no fuller approach to mapping her inspiration on his work. In the fascinating 2012 essay, “Me and Dambudzo,” Flora confesses that her public persona as the Marechera expert had been, up to that time, carefully separated from the fact of their sexual entanglement.

“I first met Dambudzo Marechera in Charles Mungoshi’s office. They were drinking vodka,” Flora begins her tell-all. Mungoshi is Zimbabwe Publishing House (ZPH) editor at the time while Flora, a German expat wife, is finding her feet as literary journalist. Dambudzo hits it off with her, what with his Oxford affect and their leftist common ground. Five years older, Flora may be a good candidate for resolving Dambudzo’s mother complex. In turn, she looks at Zimbabwe as the place to throw off her German apron. Both lovers brand themselves as good listeners, especially since Flora is a journalist and Dambudzo is always looking to write about an artsy White woman.

While Flora’s expat confidant urges her on, and her husband welcomed Dambudzo into their Harare home, even arranging him gigs to supplement erratic royalties, Black Zimbabwean sisters are not so liberal. “In the sordid city hotel, where we spend one night, all the black women stare at me. In the morning I find a window of my car smashed,” Flora remembers. At another hotel, Flora’s White face stands out, inviting strange looks and vulgar Shona comments.

Flora sees Dambudzo from October 1983 to August 1984, when her family visits Germany for a month. “When I return from Germany in September 1984, Dambudzo is distant. He believed I would never come back. He has another girl, a blonde woman,” Flora says in possible reference to Karen. “Soon she is gone, teaching somewhere in the rural areas.” Both Flora and Karen would have been Dambudzo’s lover-patrons during the production of Mindblast. Parts of the book were written in Flora’s house before she left. While Dambudzo credits Karen as the Olga of Mindblast, Flora is an important hand in the whole business.

Literary widow

College Press editor, Stanley Nyamfukudza, leaves the Harare journal out of his final draft, worried about potential libel. Dambudzo will have none of it. “Together with Flora Wild, they wore me down and it was as much as I could do to restrain myself from asking her how she came into the affair anyway,” Nyamfukudza remembers. “I finally conceded.”

Flora has a share in Marechera’s tortured love poems, and a plausible claim to the title of literary widow. Her able work on his estate and her literary criticism has been, for her part, an never-ending love poem for Dambudzo. For part 2 of this mini-series, we look into the fascinating figure of Amelia, immortalised in Marechera’s posthumous poetry collection, Cemetery of Mind. The erotic sequence was written in 1984, during the Mindblast book cycle, possibly intended them for a separate book. Can Amelia be positively identified? Is she an amalgam? We take it off from Drew Shaw and John Eppel’s famous debate on the sonnets.

Leave a Reply