Alick Macheso is the Last of the Last – He Could Use More Ambition

Appreciating an era for itself, Macheso is not entirely the deadbeat innovator between 2012 and 2018. Kwatakabva Mitunhu (2012) has a rawer, stage-like feel somewhat designed to grow on you in a cold bar or lonely drive into the night. “Macharangwanda” dips into sultry minimalism not usually associated with Macheso, while “Zvipo” rides full blast on his lived philosophy of “Nothing is impossible.”

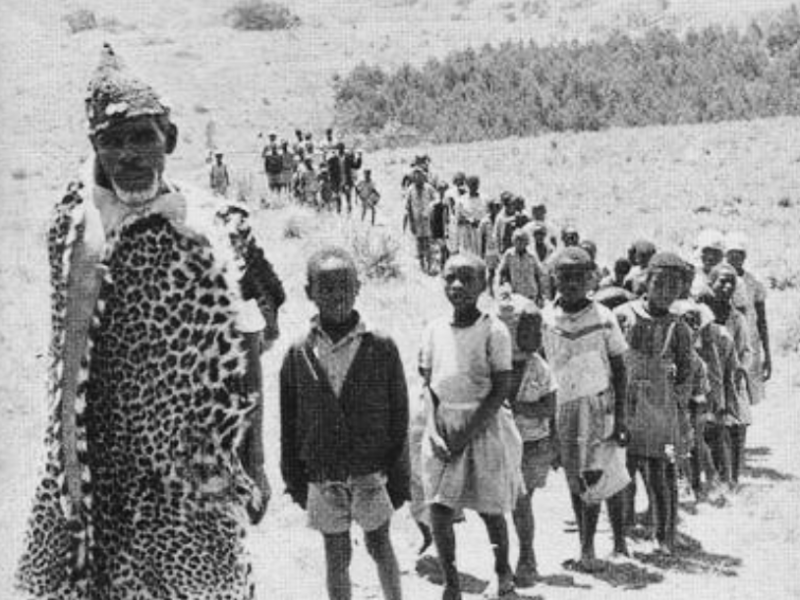

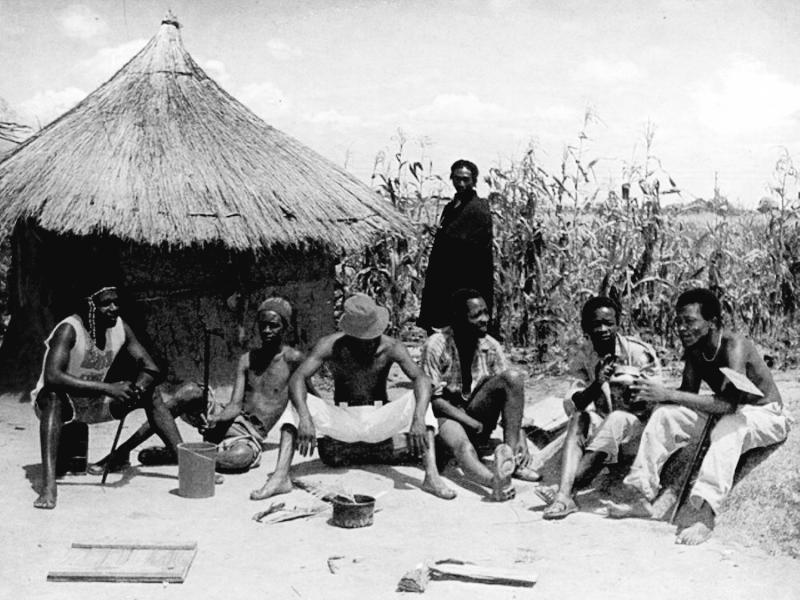

Christmas in Rhodesia was a roast roadrunner affair, started with grocery bread in a winnowing basket and finished with beer gourds passing hands around a smoky hut. At one Shamva farm, though, it was little Aleke who owned the holiday. Already famished like a scarecrow in the August wind, Aleke had made things worse by giving older farm boys his food in return for guitar lessons. Just the weight he needed for low-key pirate operations, as he now went about stealing fishing lines for his guitar strings, and disappearing into the bush with his tin fingerboard and his loot. Aleke’s notoriety was forgiven at Christmas gatherings where his weightless dance moves had farm workers throwing him their money. He left to jam with city boys at 15, was a Sungura pillar at 22, and became the king of Zimbabwe at 32. Decades later, Alick Macheso is still the humble hero of the workingman. His band, Orchestra Mberikwazvo, is meaningfully nicknamed the Band of the People and he is the Harare scene’s most obvious father figure after the death of Oliver Mtukudzi.

But Zimbabweans are least generous with their legends. Some barbershop historians feel that Mtukudzi only flourished after Thomas Mapfumo was forced into exile. Other compatriots go so far as to say Tuku was the beneficiary of an AIDS pandemic that killed the bigger artists in the 1990s. Both their hypotheses don’t seem account for Tuku’s international success. If Tuku is questioned on his contemporaries’ account, the Macheso is questioned on his fans’ account. Call girls lament that clients with deep pockets came out to watch Tuku. Left at the mercy of Macheso fans, they now have to lower their bargain. Chesology critics also include Thomas Mapfumo, who has gone at Macheso, not once but twice.

In the early years of his American exile, Dr Mapfumo was taunted by a Blacks Unlimited band member: “Macheso is now making more money than us back home.” “Anosvikepi nemabearer?” (How far will go with the bearer’s cheques?), Mapfumo reassured his guitarist. Zimbabwean millionaires buying Macheso’s albums were not quite millionaires: Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe alchemists’ first experiment in fake money would be bad news for Macheso’s bestseller streak. At his friend Tuku’s funeral, Mapfumo lamented that Zimbabwe had lost its only international artist, with the exception of, well, Thomas Mapfumo, and now the country was left with the likes of Macheso who only go so far as Britain.

Communist jeremiads of revolution to come are the music of Financial Gazette-reading “blacks in national costume” and Pan-Africanist dashiki who eat “impeccably African food recommended by The Guardian.” Chesology, with its domestic concerns of love, family and rivalry, is the preferred music of the working masses. Here again is a beautiful paradox.

Sungura A.D

My favourite school of Chesology detractors says Macheso has gone soft in his middle years. That, as an album artist, he has been washed for the part 10 years. How did we get here? The theory goes that Macheso’s fiercest rival, Tongai “Dhewa” Moyo, died with all the competition in 2011, leaving Macheso too relaxed for his own good. Sungura owned 2010 with Moyo’s Ndiro yaBaba, Macheso’s Zvinoda Kutendwa, Kapfupi’s Juice Card and Sulumani Chimbetu’s Non-Stop. Sungura A.D (After Dhewa) found the great one too bored to compete. After all, Sungura’s third stream has been mostly peopled by Macheso imitators and forgettable poetasters.

The theory holds up. Look at Macheso’ album titles since 2011: Kwatakabva Mitunhu (“We Travelled a Distance”, 2016), Tsoka dzeRwendo (“Footprints of the Journey”, 2016), Dzvinosvita Kure (“Distance Conjurers”, 2018). There is a sense of distance in all these titles, but this is distance in the retrospective rather than the aggressive direction. If Macheso is the immovable one, as he has us believe on “Gungwa” (2016), we know that because he is telling us rather than because he is showing us. Yes, he is counting the things he brought to the game and he did bring the passion of the guitarist, the bass solo that speaks any language from otherworldly sax to heavy metal death, signature Sungura dances and all that but he is not quite switching the game this time.

Appreciating an era for an era, Macheso is not entirely the deadbeat innovator between 2012 and 2018. Kwatakabva Mitunhu (2012) has a rawer, stage-like feel somewhat designed to grow on you in a cold bar or lonely drive into the night. “Macharangwanda” dips into sultry minimalism not usually associated with Macheso, while “Zvipo” rides full blast on his lived philosophy of “Nothing is impossible.” Fans still find one track or another with nostalgic claims on them from the eight years of Macheso’s ups and downs: nasty divorce, disintegration of Orchestra Mberikwazvo, competition from dynamic urban movements, family sorrows and the gradual reconciliation of Sungura’s creme de la creme.

Dead Spiral

Now, one mustn’t go blaming all cracks in Chesology on Sungura A.D. Art has always been a circuit fed by the negative of death and the positive of sex. The artist depends on a minimal anti-libidinal withdrawal from lived chaos to make sense of it all. But primal currents find him out where he least expects them. Dambudzo Marechera neatly sums up the situation: “A writer drew a circle in the sand and stepping into it said ‘This is my novel,’ but the circle, leaping, cut him clean through.”

Things that happen to a young artist will find his older version all caught up. A twisted and bleeding playboy and rockstar in his younger years, Macheso had so much to write about love and hate, family and guilt, faith and aggression. He sailed much too close to the wind, fearlessly daring industry rivals, and naming girlfriend after girlfriend in songs presented to everyone else as righteous sermons of love and marriage. He was a convincing moral philosopher, not least because he composed to the audience of his closet vices. As a poet, he had his day, scrapping together real-time proverbs for the great Zimbabwean songbook.

Then he grew up. His songs became taught life rather than lived life. Something you couldn’t place your finger on was lost.

Pools in the Tar

Macheso is the philosopher of time. When Rise Kagona and Marko Sibanda helped him form his band in 1997, he was always going to be the underdog in the high day of Dendera and Zora, the Sungura variants that owned the 1990s, and slightly out of place as old masters closed a Zimbabwean millennium with a bang. If he was not thinking through the pressures, he would not have named his band Mberikwazvo, which loosely translates to “time will tell.”

Asked about the meaning of his band name, he had different answers for two occasions. First, that he was leaving it to the future to spell out the fortunes of his new band; second, that Mberikwazvo is a band that is moving and the point of the journey is not to arrive. It’s young Ngugi wa Thiongo who wrote about pools in the tarmac: you see them slightly ahead; they may even provoke your thirst on a long journey; you arrive where they were and they are still slightly ahead. That’s how the Orchestra Mberikwazvo journey was planned.

The first thing you loved about Macheso was his art of the album. His architectural album names, Magariro (“Living”, 1998), Vakiridzo (“Maintenance”, 1999), Simbaradzo (“Consolidation”, 2000), Zvakanaka Zvakadaro (“Good Like That”, 2001), Zvido Zvenyu Kunyanya (“As You Like It”, 2003) were not just verbally incremental; they accurately reflected how he was peaking and outdoing himself album after album. It took Tongai Moyo to check him in 2005 and introduce balance and unpredictability to one of the fiercest and most productive rivalries in Zimbabwean music.

Chesology tracklists from the peak years were a running poem. There were things you looked for. Like how the last song compared to the impossible banger which opened the six-track cassette. A comparable weight, the last song would chart (“Mundikumbuke”), become a folk traveller (“Zvimiro”) or a concert favorite (“Charakupa”). The second song had to be high-octane rhumba in different languages, and the third song, a laid-back reflection, with substantive prefix “ku…” in the title (“Kusekana kwanaKamba”, “Kumhanya Kuripo”, “Kuhwereketa”) to highlight the philosophical intentions of the song.

In 2020, Macheso had to sound out his lockdown proof of life. His only loose singe to date, “Zuro NdiZuro”, coincided with Christmas after a two-year silence. Aleke reminded us that he was still the chosen one, “Macheso chete ndiye; naMacheso tinosvika,” and that he was the “tape measure” against whom other musicians will be tested. Mostly flat and predictable, “Zuro ndiZuro” (“Past Is Past) might have been also a self-aware response to people demanding the Macheso of old. Could this mean he had finally remembered to chase the pools in the tar?

New Dancing Lessons from God?

On his 54th birthday in June, Aleke had Seke Road jammed as thousands turned up for his album launch at Aquatic Complex. Lax security saw the stage swarmed by adoring fans as the legend was showered with gifts and blessings. For the album name, there was a sense of distance again, perhaps a leap into the future this time. “Peculiar travel suggestions are dancing lessons from God” so Macheso’s new album title, Tinosvitswa Nashe, declared that “God is taking us there.”

Sungura barbershops picked on his awkward imitation of Leonard Dembo’s Tinokumbira Kurarama album cover, setting off legacy comparisons. Two weeks later, Macheso disciple Mark Ngwazi came out with a brilliant album, Nharo nezvineNharo, setting off another round of unfavourable comparisons

If Tinosvitswa Nashe is not a return to form, it is a return to formula. Macheso has not released another Zvakanaka Zvakadaro but he got few things right on his new album. He has improved on the wobbly mixing of previous albums though he can still be cleaner. Deeply felt moments on the 51-minute record include “Kutaridzana”, a possible reference to his daughter’s failed marriage. “Imfa Nimulandi,” a dirge for the dearly departed is an instrumental masterclass, while “Munhumumwe” is commendably silly, an attempt by Macheso to free his hand from the flat moralisms of the past few years.

Born a king, Aleke’s robes had become too familiar by the time they fit him. With more aggression than retrospection, he can still take Sungura to new frontiers. Editor Chatora, I need to sign off with this poem for my boyhood hero:

ALICK MACHESO

Plug the bass and I will create the truth

When wire thunders, forget about a truce

I am just a farmhand with fingers of a god

Genius is the terror bursting your earpods

I come from the land of moonshine rock and roll

Lead showers same time love is decreed at a sungura show

Death is just another backstage, brother Cephas

Look for Fanuel and play the ancestors our cyphers

Smoky dreams under the thatch of migrant labor

When the cool night was all there was to savour

Sent me away with the world in a tin guitar

To bind workingmen in the holy cords of Khiama

Look over your shoulder, Madzibaba Nicholas

You gave me the front seat of our tour bus

Steadying my hands to take us into the future

Wherever I decree now, your teachings feature

If you see Mushava write, passionate to a fault

Remember he too found his voice in my vault

Twelve and enchanted in Muzokomba Township

My wires spoke spirit into his penmanship

What you overhear when guitars converse

Are the lost languages of a griot universe

At album three I had made the Sungura trinity

But Mberikwazvo is still outbound to infinity

Leave a Reply