Beyond Big Man Palaver: Pan-Africanism in 2022

The idea of an Africa that nobody takes seriously sits well with the motivations for extractive capitalism, refusal to account for black death, and racism in the Western scientific establishment, down to harmless pleasures like National Geographic authenticity porn. The proven answer to this idea is Pan-Africanism.

r Zimbabwean finance minister, Ariston Chambati, told Strive Masiyiwa about the time he confronted Henry Kissinger on the sidelines of an international summit. He wanted to know why the American diplomat had left Africa out of his report on world economies. “Unless you Africans begin to take yourselves seriously,” Dr. Strangelove reportedly answered Cde. Chambati, “Nobody will take you seriously.”

The idea of an Africa that nobody takes seriously sits well with the motivations for extractive capitalism, refusal to account for black death, and racism in the Western scientific establishment, down to harmless pleasures like National Geographic authenticity porn. The proven answer to this idea is Pan-Africanism.

Pan-Africanism means we will do it ourselves by doing it together. It grounds economic advancement, political liberation, cultural self-determination and territorial integrity in the unity of all African people on the continent and its diaspora. We have become used to thinking about Pan-Africanism the same way we think about communism and nationalism. As grand narratives loved by dictators and disproven by practice. And, for many young people born after independence, the African Dream means finding life outside the continent.

It’s easy to think about Pan-Africanism in the context of decolonisation, and as such, to see it as an idea that had its day. That may be only because it is the one time Pan-Africanism was at its most functional. “For too long we have had no say in the manner our own affairs are run or in deciding our own destinies,” Kwame Nkrumah once said. “Now the times have changed and today we are masters of our own fate,” he declared, suggesting that decolonisation had merely defined the coordinates in which Pan-Africanism now had to play out. Nkrumah’s words lose half their validity when one considers that the “we” of our time is not so much colonised subjects but systematically disempowered citizens.

Pan-Africanism is the state philosophy of independent Africa. The African Union has committed to resolutions and timelines that point the continent in the right direction. But nothing is in place for the AU to directly intervene in our everyday commons, and account for Pan-Africanism’s net effect on the lives of ordinary Africans. Nothing less than a stronger AU with regionally binding decisions, under the democratic scrutiny of citizens can take back our commons from the partisan cartels who currently own them on behalf of shadowy investors.

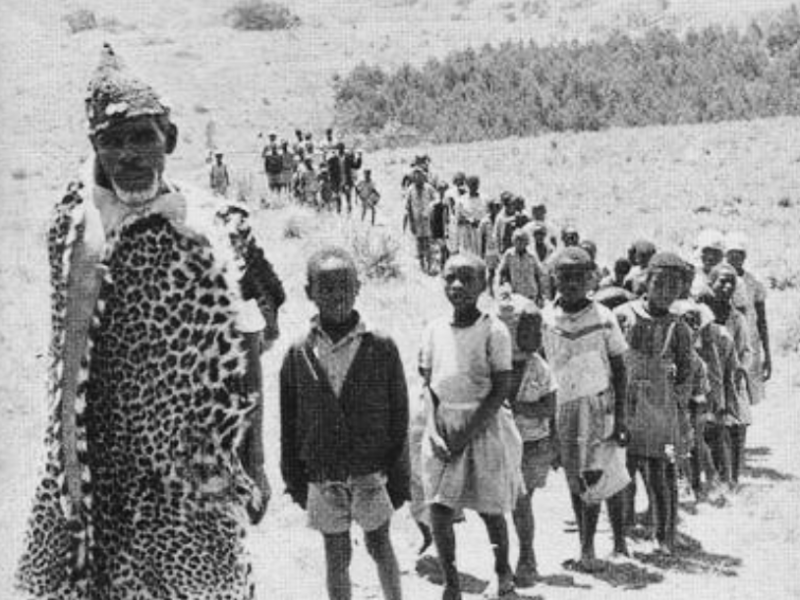

Nkrumah famously dedicated Ghana’s independence towards decolonising the rest of the continent. The Organization of African Unity (OAU), formed on this day, 59 years ago, carried this out to the end, even as the liberated countries hosting freedom fighters from the colonies invited economic and military retaliation on themselves.

Pan-Africanism was born a language of pain, brought about by slavery, colonialism, apartheid and discrimination. “Despite the boundaries that separate us, despite our ethnic differences, we have the same soul plunged day and night in anguish, the same desire to make this African continent a free and happy continent that has rid itself of unrest and of fear and of any sort of colonialist domination,” early Pan-Africanist martyr Patrice Lumumba cried out.

Later visionaries like Thomas Sankara saw that the fight had moved to the battlefield of the stomach and the battlefield of the mind but many African presidents were preoccupied with whom to give back their countries to, the French, the American, the Russians and so on. By the time OAU became AU in 2002, less than a decade after South Africa became free, it was necessary to shift the coordinates of the struggle.

African Renaissance

In 2013, 50 years after the formation of the OAU, the AU adopted a policy paper, Vision 2063 – The Africa We Want. “We all recognize that Africa’s aspirations of lasting peace and prosperity still remain to be realized and the vision of our founding fathers is yet to be fulfilled,” the AU chairperson Hailemariam Desalegn told the comrades. “It is my earnest hope that by 2063 (hundred years from the formation of OAU), we will have a continent free from the scourge from conflicts and abject poverty,” he added.

Since 2013, the AU has also passed 0.2% import tax levy on member states to finance its programmes and policies, begun work on the African Continental Free Trade Area, and proposed the free movement protocol. The AU has also moved towards gender equality in leadership, and started regulating relations between the AU and the eight regional economic communities, as well as other gains Babatunde Fagbayibo outlines in the article: Pan-African integration has made progress but needs a change of mindset, in The Conversation. There have also been efforts to work more closely with members of the AU’s Sixth Region, the Africa Diaspora, although failure to fully integrate African like Haiti suggest a structural flow.

African leaders are currently meeting to discuss the impact of COVID-19 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine on the continent, which has supplied food supplies, among other things. An internally synergised, self-sufficient and self-determining Africa will be better prepared to handle future shocks. In 2020, following the outbreak of COVID-19, dozens of African intellectuals wrote an open letter to African leaders that is even more relevant today.

“The coronavirus pandemic lays bare that which well-to-do middle classes in African cities have thus far refused to confront. In the past 10 years, various media, intellectuals, politicians and international financial institutions have clung to an idea of an Africa on the move, of Africa as the new frontier of capitalist expansion; an Africa on the path to ’emerging’ with growth rates that are the envy of northern countries.

“Such a representation, repeated at will to the point of becoming a received truth, has been torn apart by a crisis that has not entirely revealed the extent of its destructive potential. At the same time, any prospect of an inclusive multilateralism – ostensibly kept alive by years of treaty-making – is forbidding. The global order is disintegrating before our very eyes, giving way to a vicious geopolitical tussle. The new context of economic war of all against all leaves out countries of the Global South so to speak stranded. Once again we are reminded of their perennial status in the world order in-the-making: that of docile spectators,” said the scholars.

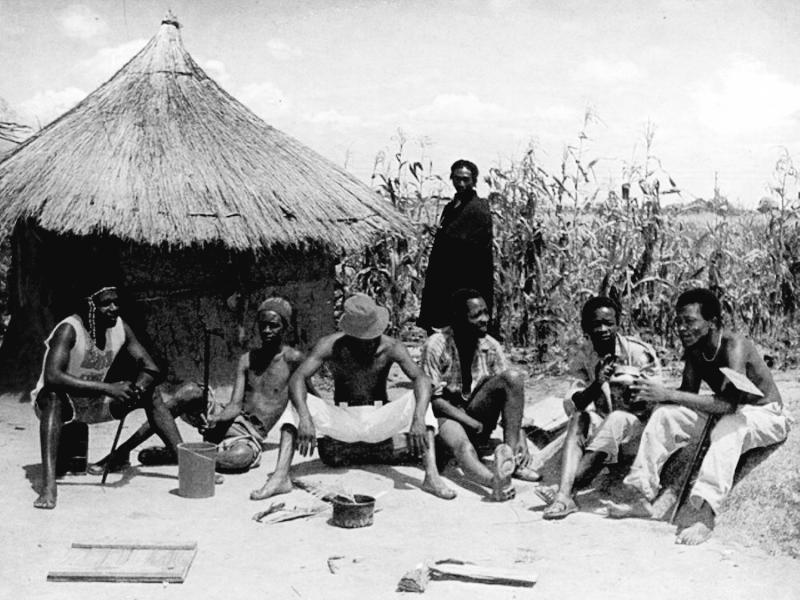

Food-insecure, healthcare-deprived and economically precarious citizens exposed to all manner of external shocks show that the Pan-African dream remains to be realised where it matters most. Shortly before his country’s independence, Nkrumah pledged: “We shall measure our progress by the improvement in the health of our people; by the number of children in school and by the quality of the education and by the availability of water and electricity in our towns and villages and by the happiness which our people take in being able to manage their own affairs.” This remains to be realised in much of Africa.

Ordinary citizens are not only vulnerable but their very precarity is a patronage card for governments narrowly committed to partisan and temporary interests. It is easier for the same governments to sell our countries to extractive capitalism, deindustrialisation, environmental rape, systematic inequality, and partisan wars, always to be suffered by the poorest, than to genuinely pursue solutions from within Africa.

Meanwhile, AU and sub-regional blocs continue to help the abuse of democracy and human rights by member governments, deflecting attention from these to the grander narrative of resisting interference.

Meddler powers have maintained a colonial chokehold on Africa, from prospecting to military and financial rights, because we left Pan-Africanism to leaders who serve their metropolitan prefects more than our people. Paltry royalties for oil and minerals, worsened by the human cost of displaced and poisoned Africans, make the idea Pan-Africanism more urgent than ever.

Leave a Reply