Drunken Piper – King Kwela Spokes Mashiyane

While Mashiyana’s kwela scene and Bob Dylan’s hippy scene both emphasised getting stoned, there was an important difference. The Doors frontman Jimmy Morrison has described the 1960s hippy movement as a middle-class cultural scene that came out of America’s post-war surplus, while Bob Dylan has an ironic response to the folk purists that booed him at the Newport festival, “I mean they must be pretty rich, to be able to go to some place and boo. I couldn’t afford it if I was in their shoes.” Getting drunk in South Africa was, however, the criminalised and exploited black body’s escape from itself. Kwela is pennywhistle-driven, with understated support from drums and an acoustic guitar. It is played to the colors of sunset, with dream-like variations to get lost to. The melody gets passive-making and unbearable but it must be resolved by touch-happy dance moves.

Spokes Mashiyane and Bob Dylan went to the most infamous folk music festival in history between July 22 and 25, 1965, and shared the Saturday night setlist. Billboard magazine described the South African pennywhistler’s swingy beat as the unscheduled highlight of the night. While folk music aficionados were digesting the leftist tropes tied to the genre and soaking up the sounds of the big remote, from Portuguese ballads to Nigerian deconstructions of Tarzan, one man was secretly plotting to disturb the peace. On Sunday night, 24-year old Bob Dylan headlined Newport Folk Festival in motorcycle black with a loud rock band in tow and desecrated the Mecca of old-style music purists. The crowd booed its heretical prophet, his new songs nothing like the counterculture commitment and unplugged intensity of his 1964 performance. Towards the end of the Sunday night setlist, shocked organisers brought up performers off-schedule to lull the crowd back to its disturbed dream. Spokes Mashiyane got his second crack at glory.

An American record label thought to cash in on Mashiyane’s well-received performance with a mouthfully titled LP, Spokes Mashiyane – The Amazing African Who with His Pennywhistle Stole the Show at the Newport Folk Festival. Back in South Africa, the piper from Mamelodi did not waste memories of his trip either, referencing America on his new songs, “New York City” (1965) and “5th Avenue” (1965). Four years later, “Newport” (1969) and “America” (1969) would be upbeat remakes of early Mashiyane songs, whistled against the full-throated canvas of mbaqanga. Spokes was at the end of his career, grappling with a monster of his own making. A decade earlier, his odd sax experiment, “Big Joe Special” (1958), had helped create mbaqanga and mark the end of days for kwela. King of the Pennywhistle (1969) would be his last album. A project report as such, naming his big hits, big visits and big moves. Newport, “Ace Blues”, even the parricidal rasp of mbaqanga in the background, made that last tracklist for the same reason.

There were two more potential use cases for Mashiyane’s American souvenirs. In Africa, we listen to our music through the ears of Western tastemakers. A folk musician overshadowed by trends at home may score better luck with foreign audiences. When foreign appeal has been demonstrated, it cycles back to a new level of cool back home. This has been the case for artists as varied as Mahlathini in South Africa, Oliver Mtukudzi and Mokoomba in Zimbabwe. Mashiyane had already been using his big-city endorsements for marketing leverage eight years prior to the Newport Folk Festival. American pianist Claude Williamson gave his word in the liner notes of “Kwela Claude” (1958): “The Kwela Rhythm, born in the craddle of Jazz, is unlike any other I have played. It could well take its place alongside Calypso and the Samba.” And then, in apartheid South Africa, a metropolitan resume would have been useful for appealing across the race dichotomy. Working in a genre of places and moods with bird-like mileage, Mashiyane’s pennywhistle took him anywhere he pleased, from next-door tsava tsava and majuba to offshore blues and jazz. He scored a series of quick firsts in the process of getting butterfly-pimped by white South Africa.

Bob Dylan. Photo credit: Xavier Badosa. Flickr/Attribution (CC BY 2.0)

However, it was Bob Dylan who gave the 1965 festival its enduring mythology. Years after desecrating the Mecca of folk music with his blues-rock set, books are still being written around “The Electric Dylan Controversy”. As it turned out, the Newport controversy had only started Dylan on a combative path with the zen, nostalgic, gatekeeper and phillistine sections of his crowd. He would stare down at his hostile public and relentlessly electrocute it. As recently as 2012, Dylan was still smarting from stale beef and Judas jeers from the era: “These are the same people that tried to pin the name Judas on me. Judas, the most hated name in human history! If you think you’ve been called a bad name, try to work your way out from under that. Yeah, and for what? For playing an electric guitar?”

But Dylan’s resentment would have been its rawest in 1966. He not only missed the Newport festival that year, and every other year until he came back to perform with a wig and a fake beard in 2002, perhaps his ironic gesture to the purists, but also vented on the events of 1965 in his song, “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35”. The lyrics pictured ancient forms of persecution right up to Dylan’s reason for writing the song, “They will stone you when you are playing your guitar/ But I would not feel so all alone/ Everybody must get stoned.” Of course, the idea that “everybody must get stoned” worked on two levels during the psychedelic 1960s, as did “rainy day woman” which was hoodspeak for ganja. Bob Dylan had already given the hippies anti-war songs and civil rights songs. Now he was giving them a song about getting high, another popular sacrament of the movement.

Istokvela hippy

Well-removed from America’s hippy scene, Spokes Mashiyane nevertheless knew everything about getting stoned, or at least, getting drunk. One of his first four recordings, “Skokiaan” (1954), inspired by the widely covered 1954 reprise of Zimbabwean saxophonist Augustine Musarurwa’s 1947 song by the same title, spoke to a theme that would be central to South African music in the decades to come. Zimbabwean historian Mhoze Chikowero puts it this way:

“Skokiaan” was an underclass counterdiscourse that contested the colonial state’s criminalization of an emergent urban African cultural economy that revolved around music, dance, and the independent brewing and consumption of alcohol. Africans responded to the criminalization of their beer by concocting a rapidly brewed drink, chikokiyana, or skokiaan in ghetto parlance, which they fortified with all manner of intoxicants. Musarurwa’s song “Skokiaan” was therefore a metaphor not only for the tenuous existence and quick wit that African urban life demanded, but also for the popular African cultural contestation of discordant colonial modernity’s attempts to reproduce and control racialized underclass African being both physically and ideologically. This contestation gave the brew its many coded monikers, not just chikokiyana and chihwani (“one-day”), but also the boldly declarative chandada, “I do whatever I like!” (Mhoze Chikowero, African Music Power and Being in Colonial Rhodesia, 2015).

Spokes Mashiyane album cover entitled Spokes Hit Parade No. 1

While Mashiyana’s kwela scene and Bob Dylan’s hippy scene both emphasised getting stoned, there was an important difference. The Doors frontman Jimmy Morrison has described the 1960s hippy movement as a middle-class cultural scene that came out of America’s post-war surplus, while Bob Dylan has an ironic response to the folk purists that booed him at the Newport festival, “I mean they must be pretty rich, to be able to go to some place and boo. I couldn’t afford it if I was in their shoes.” Getting drunk in South Africa was, however, the criminalised and exploited black body’s escape from itself. Kwela is pennywhistle-driven, with understated support from drums and an acoustic guitar. It is played to the colors of sunset, with dream-like variations to get lost to. The melody gets passive-making and unbearable but it must be resolved by touch-happy dance moves.

But you needed a permit to drink whiskey/ So some stayed at home to brew chikokiyani

Harare proponents of maskandi, Talking Drum, tell the history of racially informed liquor laws on their 1989 song, “Mazimbakupa”, “But you needed a permit to drink whiskey/ So some stayed at home to brew chikokiyani.” A comparison between hybridised African music and hybridized African beer would not be a reach. Remember Thomas Mapfumo in the early 1970s:

During a Texan Rock Band Contest in Salisbury, Mapfumo’s band had to endure the taunts of a Rhodesian racist: “Shut up you, kaffirs! Shut up you, kaffirs!” as they played the Rolling Stones’ “Last Time.”

“Then this young man called Passmore was from Zambia – Zambia was already independent. He was offended so he jumped at the white man and grabbed his neck. He had to be unfastened by the police,” Mapfumo recalled. “That incident pained me – I don’t want to lie. I started thinking, don’t we have our own music identity as blacks? These people are now telling us not to sing in their languages. That is how I conceived Chimurenga music. I told myself that I had to find myself.” (Onai Mushava, “‘African leaders are not thinking right’ – Thomas Mapfumo”, This Is Africa, 2020).

File picture: Thomas Mapfumo performs at the Home-coming bira at Glamis Arena in Harare in April 2018.

But there was no beaten path for going back. Mbira and traditional beer belonged to the same class of items suppressed by missionaries and colonial administrators for their evocative religious associations, especially since African indigenous religion had been a moving spirit in the First Chimurenga. Mapfumo’s first group, Hallelujah Chicken Run Band, solved the paradox by using electric guitars to bring out the mbira sound, and hi-hats to reproduce the hosho sound, just as the kwela pennywhistle was a relic of Scottish marching bands used by South Africans to recapture their own flute-based old-time idylls.

Mbira and traditional beer belonged to the same class of items suppressed by missionaries and colonial administrators for their evocative religious associations…Black people were not allowed in white-only bars while their own traditional beer was criminalised

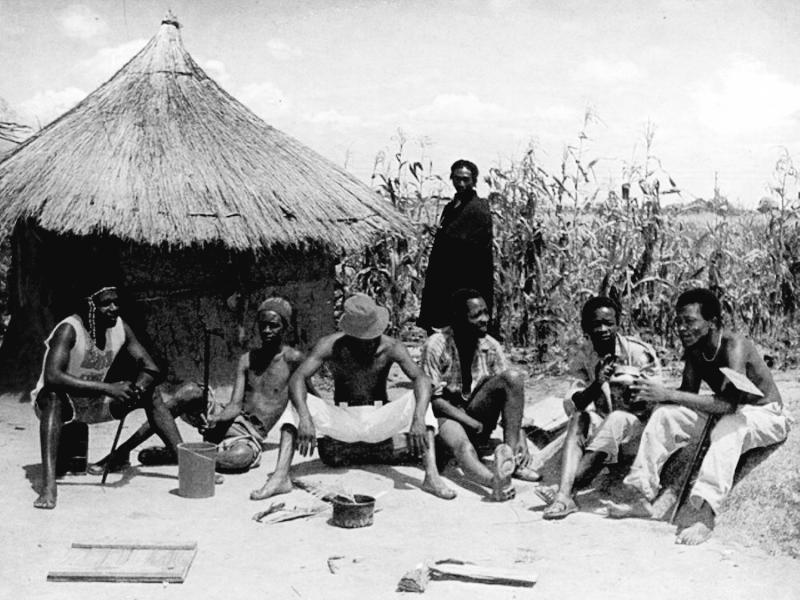

African beer had to overcome a similar paradox. Black people were not allowed in white-only bars while their own traditional beer was criminalised. They took the old ingredients to urban backyard breweries. Whereas the brewers of “seven days” in the village had balanced getting drunk with the communal, spiritual and nutritious use cases of beer (a new documentary by Hivos, Traditional Beer, Mbira and Cultural Criticality – A Zimbabwean Story touches on these), brewers of “chihwani/ one day” pumped intoxicants into the good old cornmeal liquid, maturing it to the faster dictates of city life and police chases. Beer-brewing in the ritual context of the village took an austere attitude to sex, tasking wizened matriarchs with the job. In the city, the strong-willed female entrepreneurs who took the honors had no time for the seemliness of their mothers. Panashe Chigumadzi’s 2019 essay, “Voices as powerful as guns: Panashe Chigumadzi on Dorothy Masuka’s (w)ri(o)ting woman-centred Pan-Africanism”, details the lurid business that went down at these unsanctioned gatherings.

Shebeens united the criminalised black being around beer, music, dance and sexual assertiveness. Kwela and mbaqanga were a moral outrage. The simple answer to the enigmatic riddle, “Khaqa khiqi khopo tsa satane/ He! Ka se reka” (The ribs of Satan? I will buy it), on Sankomota’s 1984 song, “Mope”, is the guitar. Religious people felt that strongly about the mbaqanga guitar but they were not alone in their dismay. When a young missus strayed from her sheltered whiteness to dance to Mashiyane’s pennywhistle, the piper from Mamelodi was dully arrested for improper association.

Mythologised around the shebeen music scene, Spokes nevertheless frequented a downtown pub for his inordinate share of the dark elixir. “Dropped off daily by his driver at the Mai Mai beerhall in downtown Johannesburg, Spokes slowly sipped his way through enough Limosin brandy to guarantee him an early grave,” recalls South African writer and kwela chronicler Chris Du Plessis. Around the time psychedelic rockstars, Jimmy Hendrix and Jim Morrison, fell to alcohol poisoning, Spokes Mashiyane succumbed to cirrhosis of the liver in 1972, aged 39.

Mafikizolo for the youth

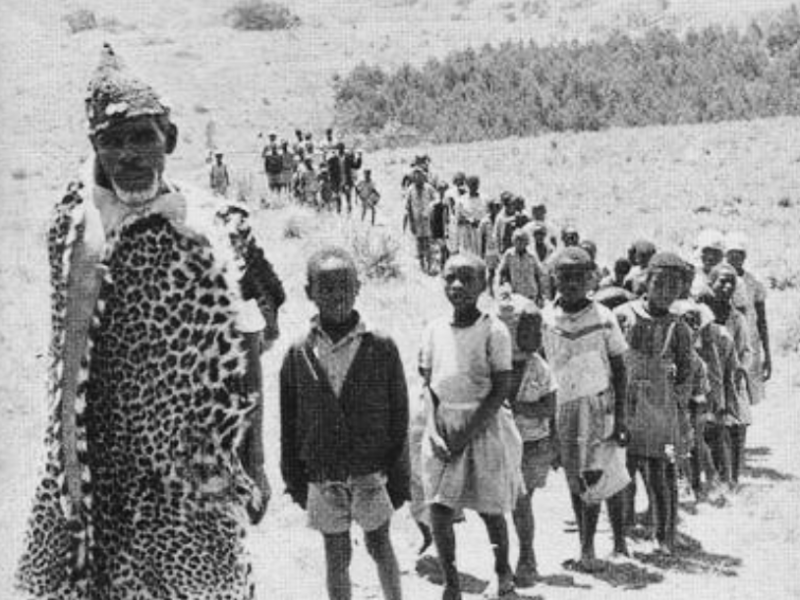

Mafikizolo’s 2003 song, “Kwela,” was easily the finest kwela primer for millenials. Its opening lyrics, “Nang’ amapolisa ayafika, Mama/ Ayangena, Mama, ngekwela kwela,” (Here comes the police; they have arrived, Mama/ They have come, Mama, in a kwela kwela) provide an etymology for the name of the genre. “Kwela,” a Zulu word for “climb,” corresponded with Babylon’s order to climb the police jeep as it raided shebeens, arrested brewers and patrons alike, and confiscated the contraband. The police jeep earned the name “kwela kwela” while the music was similarly named for its association with the precarious shebeen circuit. Pennywhistle were cheap and ubiquitous, played by young boys on street corners but especially outside shebeens where they were would be well-placed to alert the patrons that the “kwela kwela” was coming.

Mafikizolo’s 2003 song, “Kwela,” was easily the finest kwela primer for millenials. Photo: South African band, Mafikizolo. Mafikizolo-Kwela-Album-2005.

In Zimbabwe, at least, as music retreats into an idealised past, it gives off a sacred aura to be contrasted with whatever sex music and drug music is dominating youth culture at the time. It would seem our elders were not any more innocent in the 1950s. The idea that music has become a free-for-all is not new either. “Mbaqanga,” Zulu for the homemade corn dumpling, was applied to the kwela offshoot, sax jive, to convey the idea that it was cheap music that could be played by anyone, departing from the majuba big -band era. Beer songs referenced the shebeen scene decades after Musarurwa’s “Skokiaan”, notably Yvonne Tshaka Tshaka’s “Umqombothi”.

Kwela was not all booze, twin-touching and bohemia. In Du Plessis’ documentary, The Whistlers, pipers remember weekending at Zoo Lake, a zoological estate gifted the City of Johannesburg on the old proprietor’s condition that it would remain open to all people of all races, as young boys. Johannes Mashiyane, a schoolboy visiting from his home village, Hammanskraal, was found here by his soon-to-be collaborators Frans Pilime and Albert Ralulimi in playing in this sanctuary. “At first we thought it was something like a bird singing but when we looked behind the bush we saw this young boy lying on his back playing the most beautiful sounds,” Ralulimi remembers the first encounter with Spokes in The Whistlers. Spokes learnt to play on a reed whistle while herding cattle back home. He received his tunes from his dreams and favoured the simplest wind instrument for allowing him the freedom to bend his notes.

Assisted by Hugh Masekela, Mafikizolo’s song embodies the genealogy from township music to house music

Assisted by Hugh Masekela, Mafikizolo’s song embodies the genealogy from township music to house music. As we have already seen, Spokes shot himself in the foot by briefly shelving the pennywhistle to record the first great sax jive song, “Big Joe Special”. Spokes was just having fun. His notes were swingy, upbeat, with an inverted refrain. It was a whole new feel. “The record became the trendsetting hit of that year and would inspire a whole new style of music,” says a Flat International blog entry on Mashiyane. “Sax jive – later called mbaqanga – would dominate South African urban music for the next twenty years. In many ways this track marks the beginning of the eventual decline of not only the majuba big band jazz era but also penny whistle kwela itself. Younger consumers were looking for faster, heavier sounds and mbaqanga would soon satisfy those desires.” South African music has progressed in a loose genealogy from township jazz and marabi to kwela and mbaqanga to kwaito, amapiano and all the in-betweens. Mafikizolo’s Kwela album is a beautiful ancestor hour.

Hugh Ramopolo Masekela the trumpeter, bandleader, flugelhornist, compser, singer and defiant political voice remains deeply connected to home Photo: Twitter/Wits_News

Borders meant nothing to mid-century African musicians. In South Africa, eclecticism was itself a form of protest. The Group Areas Act of 1950 had prohibited Africans of different ethnicities from interacting. When mbaqanga came into play at the end of the decade, its pioneers deliberately shaped it into the amalgam of music elements from every South African region, so that brothers and sisters divided by apartheid laws were now united in one cultural expression. Music equally undermined national borders. Kwela was the negotiation of marabi, brought by Malawian migrant workers to South Africa and township jazz, a South African interpretation of the American genre. Daniel Kachamba’s Kwela Heritage Band, famed for ever-green numbers like “Maria Roza”, took kwela back to its Chewa cradle.

Borders meant nothing to mid-century African musicians. Pioneers of mbaqanga deliberately shaped into the amalgam of music elements from every South African region so that brothers and sisters divided by apartheid laws were now united in one cultural expression

Augustine Musarurwa’s “Skokiaan,” a township composition drawing on Zimbabwean tsava tsava, exercised a strong influence on Mashiyane. He not only named his earliest record after Musarurwa’s widely covered song but, according to Mhoze Chikowero, also visited the saxophonist in Rhodesia sometime before American giant Louis Armstrong who had also covered the song. Lesotho, of course, gave mbaqanga and township jazz some of its finest expressions, as well as providing homecoming turf for South African performers exiled by the apartheid government.

Spokes goes north

Mashiyane would liberally repay Musarurwa, standing with him as forerunner to some of Zimbabwe’s biggest musicians. Again, we go back to “Big Joe Special”, the sax experiment by which Mashiyane made kwela the vanishing mediator of mbaqanga in 1958. As sax jive took over from pennywhistle jive, it split two ways to high-octane instrumentals and mgqashiyo (voiced mbaqanga typically led by a bass profundo groaner). One of the brightest star of the new movement was West Nkosi, producer and in-house saxophonist for Gallo Records’ Mavuthela imprint. His sax jive instrumental, “Two Mabone,” sparked a challenge that ran from “Three Mabone” to three digits. Nkosi was the DJ Maphorisa of the 1970s, with one hand on mbube, as producer of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and another hand on mbaqanga, as the producer of Mahotella Queens and the whole host of hot new acts. The Mashiyane labelmate would soon put on a new hat as cross-country scout for Inkonkoni, another Gallo imprint. His Zimbabwean recordings of the 1970s included the bands, Tutankhamen and the Sparks, but his most enduring finds would be Zexie Manatsa’s Green Arrows band and Oliver Mtukudzi’s Black Spirits.

Oliver Mtukudzi and Winky D perform a duet at Hifa in the Harare Gardens. Photo: Shorai Murwira/This is Africa.

West Nkosi’s touch on the Green Arrows sound include guitarist Stanley Manatsa’s psychedelic fuzz effect, nicknamed waka waka by madly responsive Zimbabweans. According to liner notes for a retrospective Green Arrows LP by Analog Africa, West spoke a hesitant Zexie into recording in 1974. The resulting LP, Chipo Chiroorwa (1976), has the gendered group-within-a-group arrangement associated with South African mbaqanga. Zexie’s Green Arrows provide the music for his baritone lead while the simanjemanje-biased Black Star Sisters take over the lead on some songs, as well as shouting out to West Nkosi who is supposedly performing in Harare around the period.

The simanjemanje feel is most pronounced on Oliver Mtukudzi’s 1979 album, Muroyi Ndiani. A touch of the sixties runs through most of the album, one almost suspects Nkosi of prerecording the instruments. Outside this album, Tuku may go south on an idyllic tangent but his Korekore interpretation of mbaqanga is inimitable. The Superstar, whom Gallo Records has acknowledged as the bestselling Southern African labelmate of Nkosi and Mashiyane aside the home artists, however, cautions us against overcrediting West Nkosi for his music:

One thing about our music and South African music is that the music is the same. If it weren’t for a handful of people who created geographical boundaries, South Africans and us would be the same people in many respects. Nkosi came to produce me because he was looking for a new sound and if he was to influence my sound, he was going to get the same sound that he was running in South Africa. He wanted fresh music so he got me, Zexie Manatsa, Susan Mapfumo… all of us. My music basically continued to be the same after Nkosi had left. (Oliver Mtukudzi in Shepherd Mutamba’s Tuku Backstage, 2015)

Seamlessly sharing Azanian culture, the Bulawayo scene has not only given township jazz and mbaqanga Dorothy Masuka, Jobs Combination, The Zulu Band, The Cool Crooners, Don Gumbo and others, but has also sent artists across Limpopo to share studio time with the great neighbors, from Spokes Mashiyane to Jabu Khanyile.

The loneliness of the old-school snob

When Dambudzo Marechera wrote, “It is the ruin not the original which moves men: our Zimbabwe Ruins must have looked really shit and hideous when they were brand-new,” African music cannot have been too far from his mind. The Black Insider conversation picks up from earlier references to Bob Marley, disco-reggae and Motown soul, which go on to insist on “an Africa that would never be anything rather than artificial.” While barbershop historians like to amapiano and dancehall posters to good old times when music was all so golden, profane Marechera shows with Jose Arcadio just what substance gold is the color of.

Pan-Africanist art history, like all classical history, is a place for finding high days, roots, constants and recognitions. Pilgrims withdraw from shitty modern times to contemplate the “noblest periods, the highest forms, the most abstract ideas, the purest individualities,” as French philosopher Michel Foucault puts it. In a British bar, a tipsy Marechera persona finds himself around black artist-types in national costumes, eating African food recommended by The Guardian in the righteous ambience of reggae and soul. The image of Africa is has been fixed around performed originality. Depictions of yesterday become dictations for today.

“The underwear of our souls was full of holes…we were whores, eaten to the core by the syphilis of the white-man’s coming.” – Dambudzo Marechera, ‘House of Hunger’. Photo: Ernst Schade

But the text is not a place of origin. The word of God came to Paul saying, “The letter kills but the spirit gives life.” The classical text is a derivative that has been mistaken for an original. While the text cannot be the place of origin it can, however, be the place of innocence. Art is what passes from death to life when the artist embodies the artifice. The real artist is the one who does not know that he is artificial, just as the only Truman showman is the one who doesn’t know that he is a reality TV simp.

Majuba and kwela players looked on as sax jive swept their turf from under them. An old head named the new genre “mbaqanga” in the Led Zeppelin moment we have already seen. When his own time to be browbeat by the children came, the face of mbaqanga, Simon “Mahlathini” Nkabinde, was dismissive of mbaqanga-soul, the new bubblegum derivative taking over from mbaqanga. Billed as macho performer, main man, lion, father and so on in his heyday, forgotten Mahlathini shakes his balding head at an art form that has softened too much for his testosterone. By the time Spokes recorded his last album, King of the Pennywhistle (1969), mbaqanga had somewhat sent the pennywhistle to the museum. Although Spokes may have been more embracing of Azania’s musical dynamics than Mahlathini, the decisive rise of mbaqanga off his odd sax experiment would have remained a conflicting moment for him.

There is a Hollywood parable for the dilemma of the kwela king as he recorded his last album backed by a mbaqanga band. French director Michel Hazanavicius’ Oscar-winning movie, The Artist (2011), looks back to the decline of silent films, as talkies took over, through the spiritual crisis of an actor who embodies the dying art. Silent film star George Valentin (Jean Dujardin) finds and helps young Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo) up an acting career that soon overshadows his. She helps phase out silent films as the pioneer of talkies. George decides that he has become shit to himself, destroys his movie collection and tries to end his life. But his love-hate interest, Peppy, always shows up for him, from a deserted premiere he has unwisely timed against her sold-out “talkie of the town,” to his self-destructive gestures. At the end of The Artist, George and Penny co-star in a musical, the compromise between the silent film and the talkie, after all. And yet whatever rebound George can pull now, though, he is no longer living by his terms. His return has a touch of the Princess Mononoke (1997) paradox: “Even if the trees return, the forest is no longer his. The Great Forest Spirit is now dead.” In his 1969 return to mbaqanga, Spokes Mashiyane is an unrecognised Messiah coming back to the church of the Grand Inquisitor.

The hatred of the voice

There are few obvious parallels between our two silent masters, George Valentin and Spokes Mashiyane, but the most important one is their hatred, or at least, disregard for the voice. The silent film and pennywhistle jive are both silent art forms. When the voice invades the order of things, George and Spokes stubbornly cling to the dated instrument, equating it to authenticity. Slightly surprising if we consider the voice’s privileged place as the instrument of presence, read authenticity.

In our time, we take for granted the idea that art is a voice. For voice fundamentalists, art is nothing if not the handmaiden of politics. “If art is a voice for the voiceless, what good is the voiceless artist?” the voice fundamentalists ask. The voice reduces the distance between the imagined world and the lived world. However, it may be necessary to point out that the confusion between art and politics is a modern-day distortion. No lesser Marxists than Friedrich Engels, Theodore Adorno and Hebert Marcuse frown on the reduction of art to protest. We want to lean into art to imagine an alternative reality. But art may be better positioned to do this as a self-existing universe rather than as a conditioned speech act.

Classical snobs never seem to stand human beings for too long. Bob Dylan’s woman wants to know why they cannot live together. “I can hardly live with myself,” the man favored by muses explains. For Hegel, there got to be something haunting about being around humans: “One catches sight of this night when one looks human beings in the eye – into a night that becomes awful.” History has proven the average Pan-Africanist to be a closet Karamazov, preferring to love the neighbor in the abstract rather than at arm’s length. And then, of course, Karl Marx’s Frankfurt successors, scandalised by the fickle mob, maintain a suspicious distance from its songs. As the voice intervenes in the order of things, George and Spokes opt out of their successive generations, only making chance comebacks when the times can indulge a little nostalgia. The silent medium had opened up abstract range for the artist, sublimating sex to spirit. The invasion of the voice introduces presence porn. Voice fundamentalism has refused the silent master’s preference to be left to his dream-like purity.

History has proven the average Pan-Africanist to be a closet Karamazov, preferring to love the neighbor in the abstract rather than at arm’s length

Moody food

Spokes Mashiyane was born in Mamelodi on January 20, 1933. His quick firsts at Trutone, his original record label, included the first and the second solo LP by a black South African musician. At Gallo Records, he became the first black artist to earn royalties for his music. According to Flat International, the pennywhistle whiz’s first record label paid him a flat fee of seven to 50 dollars and sent goons on him when his asked for a bigger cut. This agrees with Tin Whistlers film-maker Du Plessis’ recollection of ruthless Trutone and Gallo scouts raiding Zoo Lake, recording young pipers all day and sending them back to the streets with few pennies for their pains. These alienated conditions may have give Spokes’ songs their moody edge. I may never be able to remember the low days of lockdown outside the idyllic-depressive ambience of “Chobolo”, “Meva” and “Dolos”, all featured on Spokes’ first LP, King Kwela (1958).

Leave a Reply