|

| Memory Chirere |

Book: Bhuku Risina Basa

Author: Memory Chirere

Publisher: Bhabhu Books (2014)

ISBN: 978-0-7974-5815-4

If simplicity is the ultimate sophistication, as Steve Jobs said, Memory Chirere may well be Zimbabwe’s most sophisticated writer.

Chirere has once again affirmed his place among the country’s most highly regarded writers, this time with his debut poetry anthology, Bhuku Risina Basa Nekuti Rakanyorwa Masikati.

As with his previous offerings, Chirere’s trimmed down, deceptively simple writing belies a range of genius. His taskbar is lined with familiar images, everyday language, all draping an incisive insight into some of life’s ironies and complexities.

The anthology comprises 68, mostly short, poems. Though varied in thematic range, the poems are traceable to Chirere not just for the characteristic simplicity but also the humour, understatement, musical effects and flippant brevity.

Chirere is at it right from the title, playing mind games with the reader as he does in what may well be this project’s fiction equivalent, Tudikidiki.

I cannot quite recollect the case he made for the latest title when he read few of the featured pieces including Shamwari Yako Saru and Tine Urombo to a warm reception at the Literary Evening last ZIBF but I am convinced it was not all jokes for him to settle for such.

Here commences my uncomfortable task. It would foolhardy to claim to transpose Chirere’s Shona to another tongue without foregoing the flavour uniquely the language’s.

But it behoves us to answer the claims of borrowed protocol, though everything cannot be retrieved to the destination for sheer exclusivity to the source.

Chirere’s title translates A Useless Book, Being Written at Daytime.

One wonders, as would the ancestors, if the poet is not being the modest mountain hiker who asks for stones from those at the base.

Not So Useless, After All

Whatever the case, being written at daytime does not make Chirere’s book less useful. Maybe the modest title points to a condition needful for all great literature.

This in that as a product of daytime, or rather everyday, concerns and interactions, the book is the emanation of a natural setting as opposed to contrived effort hence more likely to provoke a response from everyday people.

Only Chirere knows what message he had for the community in naming this fourth-born of his individual creative output.

But if the book is useless, the poems are not. Bhabhu Books editor Ignatius T. Mabasa attests as much.

Again it would be foolhardy to attempt transliterating Mabasa’s Shona. But he says something to the effect that Chirere has come of age and earned the sceptre of Shona poetry.

No mean feat considering the cloud of illustrious predecessors, Hamutyinei, Chivaura, Zvarevashe and other exponents of that late-lamented golden age.

All the same, Chirere stakes his claim to the presidium. Let us consider, a poem at a time, the gems which Chirere has minted to a, let it be said, comatose tradition.

Mashoko Ekutanga (First Word) is a preamble of a sort. Chirere queries, Tipeiwo Dariro style, why he cannot locate his name in all the books he reads.

Rhetorically, he queries why no one could remember his name or make something of his story.

Few lines into the poem, he resorts to earning his immortality by planting trees, publishing books and siring children – to write his name in verse neither marble nor gilded monuments can outlive as Shakespeare rightly predicted of his own.

Bembera (Celebration) spells out a defiant case for entrepreneurship: “When you used me/ what did I say?/ Now that I am working for myself/ what do you have to say?/ There, an idiot/ doing his own thing?”

It is homage to the next generation of entrepreneurs in an economy and a time which asks not so much for locating multitudes within establishments but disruptive innovation.

Yambiro (Advice) is a pacifist piece, desperately needful in a worldwide climate of intolerance: “It takes/ red eyes,/ and strife/ and sweat, and passion,/ to built/ an insignificant heap/ like that/ of a cricket.”

Dancehall prodigy Tocky Vibes’s Hondo Dzemanyepo (Fake Wars) comes to mind “With out-popping eyes having seen/ Like a camera having zoomed/ We chase a deflated ball.”

There remains to execute the case for expending love to all humanity instead as opposed to seeing the world in interest-coded lenses. There inheres eternity.

In Shamwari Yako Saru (Your Friend Saru) the persona is flustered by his inamorata’s friend, something close to Dickens’ said fixation with Catherine’s sister, Mary, the more literary of the sisters.

The persona indirectly outlines to Saru how her friend is awake to his needs in contrast to her, concluding that he is tied down to her by pity – of all qualities.

It is not an unusual dilemna. I will venture to throw in on Saru’s behalf the 80 against 20 percent complex, being the deceptive visibility of the sunny side of someone with whom one has not shared the travails of life commitment.

Mukuru Wekuchechi Kwedu could be a pastor or an elder. Either title, the humorous message is equally accessible.

“The leader of our church/ is now like a watch;/ he will die in people’s hands.” Gentle reader, translation will always be a headache. A watch malfunctions, a person dies – but the message has been sent and we know that the concerned clergymen are on alert.

“The leader of our church/ is like a brook without a bridge/ you only cross when it has calmed./ The leader of our church/ is like township brew/ You ask each other, ‘How is it today?’ before you buy.” It is a well-worn subject; the onus is on the leader of Chirere’s church to be more, in a word, Christ-like.

Zvematongerwo eNyika neMatongero eDetembo (Of Politics and the Power of the Poem) is a call both to consider the place of literature in statecraft and to honour fraternity before violence and self-interest.

“When you go about politics/ consider also the power of the power of the poem./ Consider also the thud of words without a scourge…/ When you go about politics/ remember the proverbs and the lore which brought us up,/ Because I do not want to find you alienated, my children.”

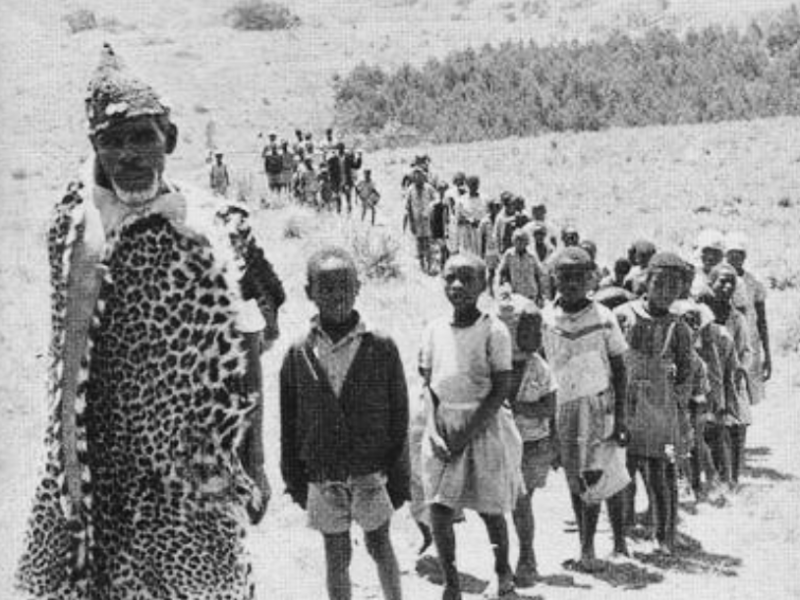

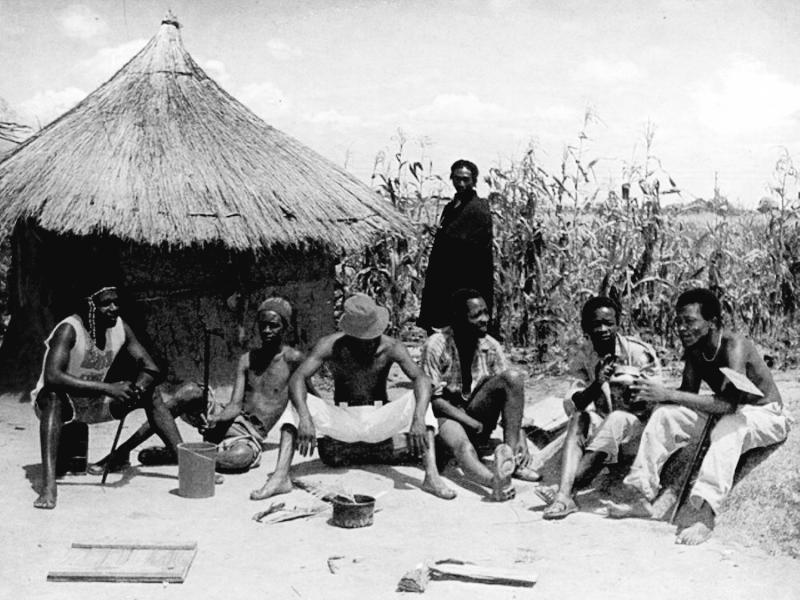

Bvunzai Vatema (Ask Blacks), an Afrocentric statement, directs the world to the accomplishments of blacks, a pertinent call considering the dehumanising tags assigned to Africa.

Egyptian ingenuity gave the world the pyramids; the Hungwe built the Great Zimbabwe. Africa is not the backyard of civilisation.

The defense counsel, however, stretches his case too far and claims: “…before heaven and earth were created, the blacks were consulted. Even before the blacks were created/ they were first consulted.” The poem is the longest of the collection, at three and a quarter pages, though pieces such as Madhara Edu are more ambitious in their flippant brevity.

A Packet for Buddies

Chirere also finds time to poke his writer-friends I.T Mabasa, Emmanuel Sigauke and Tinashe Muchuri with the poems, respectively, Mashoko eRimwewo Benzi (The Words of a Certain Madman), Karunyararo (A Silence) and Tine Urombo (We’re Sorry).

I am not sure why the Mabasa dedication is laced with issues of eccentricity. It could be because of his noted devotion to the language the mad persona is trashing.

Or because Mabasa proclaims himself to be the secretary-general of fools, after the tenor of his novel Mapenzi, acknowledging Shimmer Chinodya’s default chairmanship by virtue of the latter’s novel Chairman of Fools.

Had editors patience enough I would straddle Chirere’s Useless Book across the whole centrefold but the assignment is to be representative rather than exhaustive.

Chirere, an award-winning author and respected literary critic in Zimbabwe, is no uncommon feature on our arena. Hopefully, more “useless books” are rolling off Bhabhu Books.

Leave a Reply