Is Tocky Vibes the Next Tuku?

Talking greatness, Tuku is Zimbabwe’s answer to Bob Marley while the usual thing is to look past Tocky Vibes in the pop conversations of the day. But then a righteous parallel would necessarily go back in the day to pick up a Tocky-sized Tuku. According to Tuku’s day-one, Piki Kasamba, in the 1980s, the Black Spirits was a second-tier band compared to Thomas Mapfumo’s Blacks Unlimited or Zexie Manatsa’s Green Arrows. Whereas fans micromanaged Winky D and Jah Prayzah albums down to the last conspiracy theory in the 2010s, Tocky Vibes albums like Tirabhuru/ Kwatazonke (2016) and Rori (2018) slipped past reviewers’ notice.

If Van Choga is a drunken dragon on the stage, then Tocky Vibes is an ecological event in the studio. During the “New Dispensation” alone, Mr Vibes has already released seven projects – five studio albums, an acoustic compilation and a singles collection – besides uploading videos more often than your crush’s photoshoots. But – though we could place Tocky Vibes against Van Choga’s energy or against Van Gogh’s authenticity – one question makes more overall sense: Is Tocky Vibes the next Oliver Mtukudzi?

On his latest album, Dhongi neWaya, Tocky Vibes pays his second tribute to the late great Tuku. The previous tribute was a collaboration with Soul Jah Love whom Tuku picked, along with Tocky Vibes, as his favourite young artist. Sung over “Shanda” and “Hear Me Lord” keys, “Mudhara Tuku” repeats advice from the African superstar to the 26-year old singer not to listen to people and, equally, advice to sing for the people and to sing for keeps.

Most gatekeepers will jump at any parallel between Tocky and Tuku as blasphemy, so we may well oppose a little mathematics and history to their piety. As if it is not mathemagical enough working out how Tuku did 66 albums in 42 years – a yearly album for each of his 66 years on earth – Tocky casually dropped four projects in 2019 alone. At a conservative rate of three albums per year, Mr Vibes will have recorded 100 albums by the time he turns 60.

All Creativity, No Calculation

The immediate objection here would be: What sort of albums?

Talking greatness, Tuku is Zimbabwe’s answer to Bob Marley while the usual thing is to look past Tocky Vibes in the pop conversations of the day. But then a righteous parallel would necessarily go back in the day to pick up a Tocky-sized Tuku. According to Tuku’s day-one, Piki Kasamba, in the 1980s, the Black Spirits was a second-tier band compared to Thomas Mapfumo’s Blacks Unlimited or Zexie Manatsa’s Green Arrows. Whereas fans micromanaged Winky D and Jah Prayzah albums down to the last conspiracy theory in the 2010s, Tocky Vibes albums like Tirabhuru/ Kwatazonke (2016) and Rori (2018) slipped past reviewers’ notice.

All creativity, no calculation makes Tocky Vibes a second-tier artist. Whereas commercially attuned heavy-hitters spread their releases around charts and algorithms, Tocky Vibes works with his raw process in the open. The album title and tracklist for Rori were apparently changing in beta mode at the latest prompt, while the video rollout was unambitiously mixed with new singles. His weaker albums, including the latest one, lack a sense of cohesion and the song selection is thin on standout moments. Occasional masterpieces are left as loose singles while the ones that make the album get diluted in a sprawling tracklist.

And then his best work – Chamakuvangu (2018) was by far the album of the year in my book, and Villagers Money Vol. 1 (2019) is a good-to-great effort – comes and goes without a mainstream splash. So the good things we know about Tocky Vibes – originality, versatility, vocal range, penmanship and so on – hardly cohere into one premium package.

No Industry for Young Men

This would not be unfamiliar territory for Samanyanga. We know all the great Tuku songs because he endlessly reprised and reissued them. For example, he released no less than six retrospective compilations since Derby Metcalfe famously took over dragged him after the bag. But how many had kept the same energy with the original albums his classics arrived on: Nzara (1983), Was My Child (1995) or Ndega Zvangu (1997) for example?

If I can make a side note here: How many people confuse creativity with visibility or rather art with business when it comes to mapping the Tuku legacy? Some claim that Tuku became great after sungura icons fell to Aids; others claim that Tuku became great after Metcalfe over, and yet others, that he became great after Thomas Mapfumo left for the U.S. None of which I have found convincing. As an album artist at least, Tuku does not become great in 1998; he is already timeless in 1978.

To prove that he was always great but we just did not notice, he then released as many compilation albums as he released new albums in the 2000s, when he finally had all eyes on him, with each release solidifying his status home and away. In other words, he was playing us for not having played him. He had been deepening and broadening all along and now he had risen. It is not hard to picture Tocky Vibes on a major-label compilation few years from now, making y’all write think PhDs about songs you skipped in 2017.

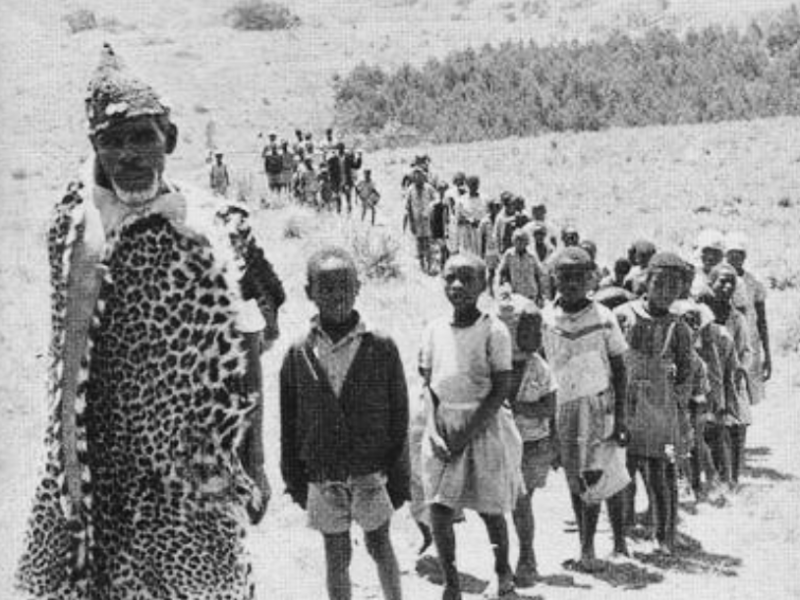

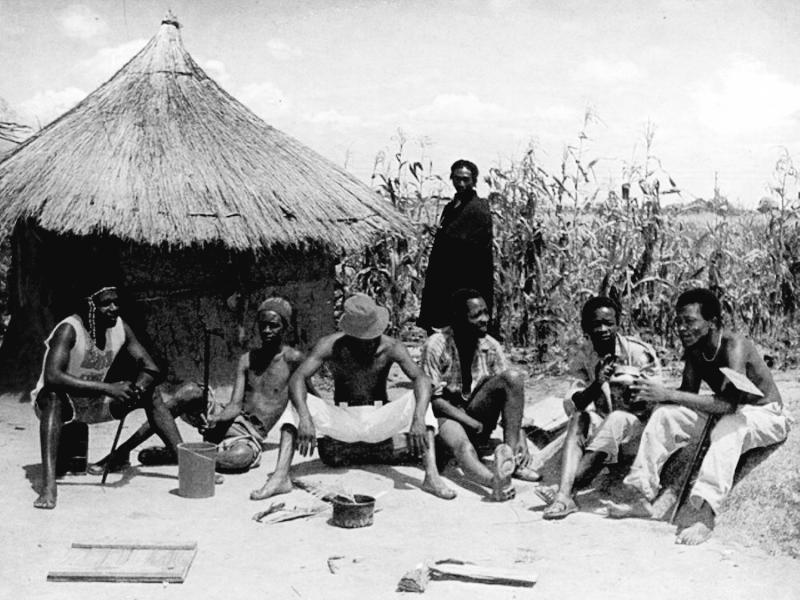

Tocky got nothing on the younger Tuku when it comes to being creatively dope and commercially questionable. Mudhara Piki recalls an era when the Black Spirits played for passion while living hand to mouth, somewhat confirming biographer Shepherd Mutamba’s recollection of a pakadoma encounter with Tuku a decade after the legend had already sung revolutionary classics.

It is said that an elephant is not weighed down by its ivory but the weight of a band sometimes got too much for the younger Samanyanga. He would wake up without a band and play through the bad days out of sheer self-belief. Sugar Pie (1988) was reportedly recorded solo, with Tuku playing everything in turn. On Ndega Zvangu (1997), Samanyanga goes toe-to-toe with Steve Makoni for album-length guitar solos, a formula nowhere near the epoch-making Tuku Music that comes a year on. Wawona (1987) is recorded with a borrowed Zig Zag Band after a band exodus and the gospel album Ndotomuimbira feels like a lonely afterthought.

Chamakuvangu equally knows few things about going it alone. In 2015, he reportedly fired his band for incompetence just before a Kwekwe show and then asked organisers how on earth they expected him to perform without a band. His glory days were just behind him after ditching riddims to explore his own sound. As showbiz panned to the next trend, Tocky Vibes was dropping career meditations like “Muroyi” and “Bhora Mutambo” in frequent batches of singles that will only make sense in retrospect. Tuku made vulnerable music too at his lowest, special art to be related with differently from sonically accomplished but spiritually detached songs that entertainers do in their peak years.

On Wawona, Samanyanga is his loneliest, if one ties the title track to Mutamba’s Tuku Backstage (2015). After an indecisive back-and-forth between Daisy and Melody, his first wife had left for good. Tuku was at the onset of a long battle with diabetes. As if the earth had not already slipped under his feet, the Black Spirits disbanded, leaving Samanyanga with nothing under the sun except his voice. The syndicated loverboy, therefore, got a lot on his mind as he resumes singing: “Ndaikufunga pandairwara/ Ndiyo nguva yawakanditiza… Siyana neni ndichawana wandinoda.” And he is probably in Kwekwe on Daisy’s heels when he gangs up with the hometown rockers, Zig Zag Band.

The title, Ndega Zvangu, is probably low-key on yet another bandless era. The album’s themes are varied from “Andinzwi” to the original “Ndasakura Ndazunza” and “Ndakuneta” but is this not the sort of thing an unacknowledged artist would sing about? Not a few Tuku years were spent alone and unnoticed. Thoughts of Harare four tollgates away might then justify a less obvious interpretation of “Kushaya Mwana” (1987): “Vana vemhiriyo kukoma/ Ndongoenda ndenga/ Ndichatuma aniko?/ Ndichangoita ndega.”

Of Katekwe and Kwatazonke

Asked to name his genre in a 2014 interview, Jah Prayzah is at his honest best: “I don’t know. Maybe you can help me there.” One thing about Katekwe, Dendera, Zora or Chimurenga is that they are all dubiously one-man genres. A hall-of-fame sound is custom-defined and Jah Prayzah just had not found a name for his. Around this period, a 20-year old Tocky Vibes was suffering from a far more costly identity crisis.

Having dominated the industry single after single, he went from the botched invention of a “ragga-marimba” genre to rocking a Nehanda wardrobe. The young star talked up heritage and originality, self-aware, if arrogant, with interviewers who sounded unconvinced by his new drift. His debut EP, Toti Toti (2015), marked his departure from signature Zimdancehall.

Mr Vibes seemed to be the only one who was unbothered by the premature end of his teenage reign, as if he preferred deepening to rising. Subsequent albums were eclectically pitched between Zimdancehall, Afrofusion, jit, gospel and reggae. He is at his most diverse on Chamakuvangu and only stays within a form on the reggae-solid Villagers Money Vol. 1 and the Vialy-assisted Toti Toti. A long look at Tuku’s career and you equally get a headache trying to place him somewhere: Is he jazz? Is he mbaqanqa? Is he traditional? Or, perhaps, gospel?

Tuku is Katekwe; Tocky is Kwatazonke. But you only get to say who you are after going to the end and finding yourself. A full-resolution panorama of your swerengoma years is only seen in rear view.

Wisdom Is Not Open-Source

Oliver Mtukudzi and Thomas Mapfumo are sometimes misunderstood as getting it all open-source because they are traditional. But as you listen more closely, they are not merely inheriting but equally deepening and complicating, both the sound and the language of tradition. Wisdom, after all, is not what is in the open but what is hidden. To be a songwriter, it is not enough to be the preacher: you got to be the poet too.

You could hear “Hakuendwe” (1995) from afar and shrug: There goes an old man who survives on proverbs. But Tuku is here bending the language to its limits. Give him two minutes and you are mystically lost in poetry by the time he is done singing: “Dai uri wembeu Mai vaikuchengera/ (Muchengo)/ Vaikupfekera muchengo pavanokuona/ (Pfee)/ Pavanokuona, kumirira bumharutsva/ (Yaturuka)/ Bumharutsva, uri wembeu here?”

An early Tocky Vibes classic like “Usakande Mapfumo Pasi” (2014) is niche material in Zimdancehall but it relies on singjaying popular sayings – proverbs and motivations – rather than on giving them an individual twist. As he progresses from novice to master, Tocky Vibes either searches for rarer sayings or makes up new ones: “Vakuru veguhwa muromo ipfuhwa rinotsva nekubika zvarisingambopuhwa” (2017). Again a heavy role for wisdom in a 2019 rhyme: “Ndakuvara pachironda/ Ndapara mhosva ndiri muboma/ Kufirwa nemunhu akandiroya,” blending new images with old sayings.

If you can tell Tuku values from his music, you can equally defend a dissertation about Tocky Vibes the humanist philosopher: “Kana hana yako ikange ichirova/ Kwete semutendi asi semunhu/ Rudo ndaona rudo/ Hana yako ikange ichirova kwete semupfumi…” (2019), pairing him with Madzibaba Zakaria, if you want, for rejection of narrow essentialism: “Mumwe ndanzwa oti ndirikurwira nyika yangu/ Ndiani acharwira pasi rose?/ Mumwe oti ndiri kurwira mhuri yangu/ Ndiani acharwira munhu wese?” (2018).

On bad days, the formula runs down to diminishing returns, with neither artist immune to esoteric or pseudo-profound lyrics. You miss the clearer Tocky Vibes when he cries out unprovoked: “Bataiwo tsumo dzakamisisa,” at the end of his impenetrable latest title track. And then, while Mr Vibes has become more convincing in his use of English, with the help of Rastaman bravado, since the days of “Daddy” (2015), he still needs to write further afield as he does in Shona: beyond popular wisdom.

Don’t Come Today and Die Tomorrow

You know there is nothing left to sing about when a generation of artists sings about singing. That’s music in the Zimdancehall era. But the routine braggadocio sometimes turns into something reflective. Soul Jah Love’s “Ngundu Ngundu” (2015) is a critique of monotony: “Wahaha, siyanisai zvinhu, boys,” while Tocky Vibes levels a total no-no to bubblegum music in ”Iyi Nziyo” (2018): “Ndakamuti usauye nhasi wofa mangwana.”

It is a marvel to watch an artist challenging himself in real time for authenticity and durability. An old Tocky Vibes album gives you that whereas most of his peers are spiritually undernourishing in hindsight. If he works out his commercial calculus, the hardworking Rugare singer will go down as one of the greatest ever to do it.

So, is Tocky Vibes the next Oliver Mtukudzi? No; he is the first Tocky Vibes.

Leave a Reply