Lovemore Majaivana’s Totem Feast

Majaivana has been received as a prophet of economic justice and regional inclusion. Less attention has been paid to the Ndebele folk tradition which grounds his protest. Most of his songs are inherited wholesale from the past and sung with a self-demeaning, if ironic, twist. In “Inyoka”, “Inhlanzi yeSiziba”, “Yingwe Bani”, “Ipholisa” and “Isambane” and other songs, it is the condemned animals, feared, hunted to the death, associated with witchcraft and excluded from nation-building imagery, that become Majaivana’s altar egos and personae. His bitterly felt tropes range from intellectual loneliness to attempted genocide and marginalisation against the people of Matabeleland.

“Namhla kulo mdlalo omkhulu okaMajaivana” (Today there is a big feast at the Majaivana homestead), folk revivalist Lovemore Majaivana sang on his Zulu Band debut, Salanini Zinini. In newly independent Zimbabwe, major artists were not only promoting the values of patriotism, work and progress, but also leaning into folk imagery to make good on their cultural nationalism. Beasts of conquest were the heroes of the patriotic songbook, while night animals represented reactionaries. The train, a new totem of progress, opposed itself to the black secrets of the forest. Rare was Majaivana’s totem feast, a gathering of the condemned, burning with the green night gaze of hunted animals.

In Zimbabwe’s folk register, animals are totem ancestors, warrior figures, dark agents and civilisational outliers. Whether hunted or condemned, animals are what humans have projected into them. The fate of animals is be tamed to the demands of civilisation, just as the fate of tradition is to become missionary language. The Princess Mononoke obituary, “Even if the trees come back, the forest is no longer his. The great forest spirit is now dead,” is not only true of animals as a captive spectacle, but also true of indigenous culture in its assisted resurrection from colonial erasure to missionary orthography.

Totems have evolved away from their gross sexuality, dark spirituality and primal aggression to become the origin story of modern times. Annotating his “tigritude” comment, Wole Soyinka suggests that British colonialism is not so much about destroying as it is about absorbing African cultures. Something of the sort becomes apparent in V.Y Mudimbe’s The Invention of Africa and, to some extent, Mhoze Chikowero’s African Music, Being and Power in Colonial Zimbabwe.

Night animal

Whom do we meet at Lovemore Majaivana’s totem feast but inyoni yezulu, the hammerkop/lightning bird hunted by witches, inyoka eluhlaza, the green mamba to be killed on sight, and isambane, the aardvark/ant-eater who digs holes that witches appropriate? Inhlanzi yesiziba, the water spirit of Njelele Shrine, and yingwe, the leopard, are benign and royal totems, but we find them spiritually out of place in Majaivana’s songs. Lost in pond and city, they extend the themes of identity and appropriation found in the songs about darker animals. Night animals, the ones associated with witchcraft, are the proverbial bad guys of the patriotic songbook. At Majaivana’s totem feast, they are nothing less than his own tall personae. How do we get here?

Two mbaqanga songs sang back to each other in 1984. When Majaivana left Jobs Combination, his old band, now fronted by Fanyana Dube, came out with “Simehlul’ uSathane.” The song taunted a fallen angel who had cool ideas before borrowed glory got into his head. Majaivana had been fired by the band’s patron, night club owner Job Kadengu, and the remaining band members were now uniting around the righteous resolve: “Masithandaneni bafowethu/ Singathandaneni ngenxa yemali” (Let’s love each other, brothers/ And not love each other because of money).

Early Zimbabwean bands were tied to mines, nightlife joints and other proprietorships. Surer of themselves, frontmen were liable to clash with the patron over pay issues. Thomas Mapfumo got the sack from Hallelujah Chicken Run Band in 1975, and Biggie Tembo from The Bhundu Boys in 1989 over financial arguments in which the lucky survivors were happy to unite against their frontman. Job’s Combination’s use of the Bible to demonise the fallen outsider made sense in a country where religion and tradition were made for material and administrative goals. The Combination’s better-remembered song after Majaivana, “Ilinga”, is a related moral parable.

Majaivana’s reply, “Isambane”, continues the play of inside and outside from the Combination’s “Simehlul’ uSathane”. In the song is master, Job Kadengu, sons, Job’s Combination, and ant-eater, Majaivana. Culturally known as a witch’s companion, the ant-eater burrows long tunnels in search of ants, making it the sort of animal a witch would need for digging graves. In the song, ant-eater Majaivana looks to be rewarded for his work but is rewarded with death instead. He questions the holiness of his comrades’ pact against Satan and suggests: “Ayathandana la madodana lomnini wabo… athandanel’ imali” (The sons and their master love each other… they love each other for money). Schemers without agency, he warns that they are next in line for the master’s mean streak.

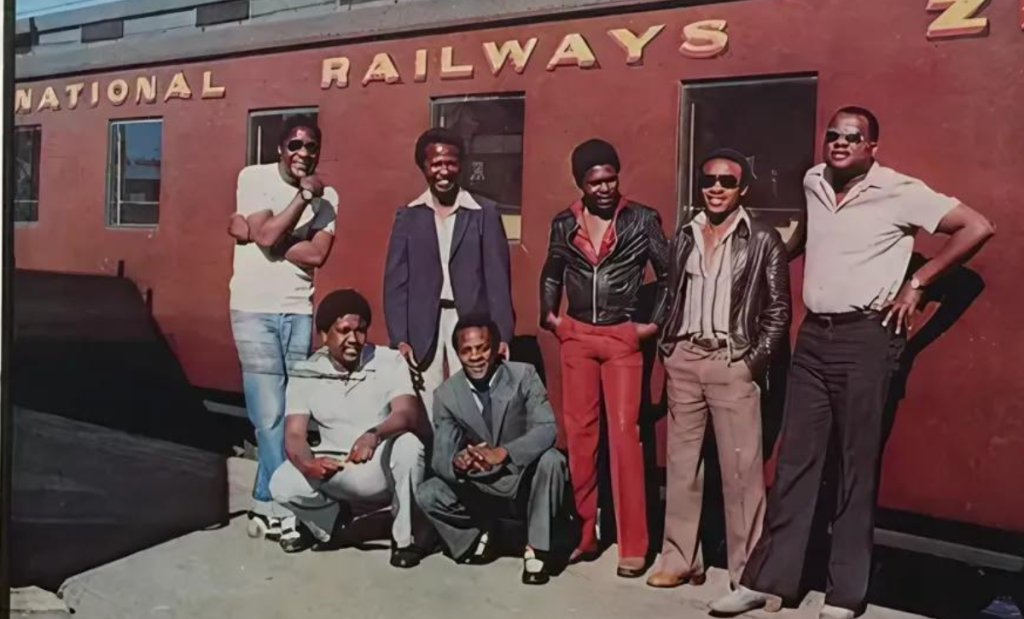

Thomas Mapfumo and Lovemore Majaivana

“Isambane” introduces a device Majaivana will often return to, not just for settling industry scores but also for making sense of Zimbabwe’s virulent tribalism. Beast of burnout, Majaivana wears the bad fur thrown his way from his first album up to the deafening pain of his last album: “Set me straight/ We may give you bad luck/ Since we are hearers of bywords.” Amazwangendaba, also the name for Majaivana’s Nguni kingdom in Malawi, hearer of bywords because they do not sit in the circle of decision. Since the one who is not on the table is on the menu, Majaivana’s totems are the hunted and the condemned. He brands himself as the industry outsider, explores abandonment issues and repeats the words of insiders with twists of irony. By not ducking evil names, he is too burnt out for duty and propriety in an exploitative setting.

Majaivana lets his animals exist for themselves and delights in their speaking agency as they evade their hunters. Inyoni yezulu comes through on “Yingwe Bani” and “Ule Nkani”, buffalo-soldier-like songs about hardened survival. It is in no way a man’s bird. As leopard, Majaivana swaggers around the city as if his spots were not made for the palace. He dares to show face where is hunted, ready to burn from his own brightness rather than be a palace souvenir. After daring witches to touch him, he chants his last word, “Inyoni yezulu yaphapha yahlala” (The lighting bird has beaten its wings and landed). A self-immolating spectacle to conclude an uncompromising career. Majaivana’s precarious totems don’t always evade their evil hunters. Inhlanzi yesiziba, the water spirit of Njelele, chokes on the mud of gentrification in one of the mbaqanga great’s most philosophical songs.

Majaivana has been received as a prophet of economic justice and regional inclusion. Less attention has been paid to the Ndebele folk tradition which grounds his protest. Most of his songs are inherited wholesale from the past and sung with a self-demeaning, if ironic, twist. In “Inyoka”, “Inhlanzi yeSiziba”, “Yingwe Bani”, “Ipholisa” and “Isambane” and other songs, it is the condemned animals, feared, hunted to the death, associated with witchcraft and excluded from nation-building imagery, that become Majaivana’s altar egos and personae. His bitterly felt tropes range from intellectual loneliness to attempted genocide and marginalisation against the people of Matabeleland.

Country-building burnout

“There are challenges he faced in the early years,” Majaivana’s friend and collaborator, Albert Nyathi, tells this publication, speaking back to the “political differences” of the 1980s. “There was, for example, a minister who would come on stage while he was performing and say, ‘Clear the stage for me to sing my Chimurenga songs.’ Of course, what that politician was saying was a sentiment among his peers,” the imbongi explains.

Around the time Majaivana recorded his first album with Job’s Combination in 1983, Robert Mugabe’s government deployed a specially trained army in Matebeleland and Midlands, thousands of civilians were killed. The Chimurenga minister would have been opposing himself to the ethnic feeling strongly expressed in the songs of Majaivana who performed in Harare most of his career. The patriotic songbook of the 1980s had been built out of a sense of ownership and optimism for the new nation. Celebrated by name on the Harare music scene, and internationally praised, Mugabe was selling a narrative of progress. Paradoxically, just three years into independence, he had turned his guns on Majaivana’s successive home provinces.

An estimated 20 thousand people were killed, indiscriminately accused of harbouring dissidents. The patriotic songbook largely ignored the reality of a nation split within itself, as Matabeleland grappled with more sorrows, including the deindustrialization of Bulawayo. In songs like “Ngenzeni” and “Khala Ntandane”, Majaivana gave his voice, the biggest to come out of the two provinces, to the suffering:

Bengise Tsholotsho mina

Ngadlula eLupane

Wo bayakhala, kabasela thando

Ngafika eJotsholo, eNkayi

Wo bayakhala, kabasela thando

KoBulawayo bayadubeka bayakhala

Working in Harare where business prospects were brighter, Majaivana found himself spiritually distant. His intellectual loneliness stretched into the distance of cultural memory. His songs breathed a yearning for things already lost. He conjured absence into a substance of its own, a new substance that could not compensate him but rather defined him by his lack. Sometimes he opposed inherited songs to their original meaning, remaining with the singular image of a lone wolf whose soul was breaking apart.

“At one time, he was in London and invited to perform in Japan. But the Zimbabwean embassy in London said: ‘No, no, no, this one is not playing proper Zimbabwean music; so we are going to have someone else. So they brought someone from Harare to go to Japan when the people in Japan needed Majaivana,” Nyathi recalls another alienating Majaivana experience. Language remains a barrier in Zimbabwean music. Conversations about musicians from Matabeleland hardly move past negation. Regret about who left the industry in protest, who got blackballed, who got canned, who is bigger abroad than home and other gestures of self-probing take the space of cultural criticism at the expense of the content.

Retired and self-exiled for the past two decades, Majaivana has nothing good to say about the music industry back home. “My life has always been a sad one. I have been dealt blows below the belt,” he opens up in an uncredited interview. “First of all, it was the language I sang in. It didn’t really bring me the fortune that one expects like when you look at these other people that sing in the widely known languages. They get a better share of the profits.”

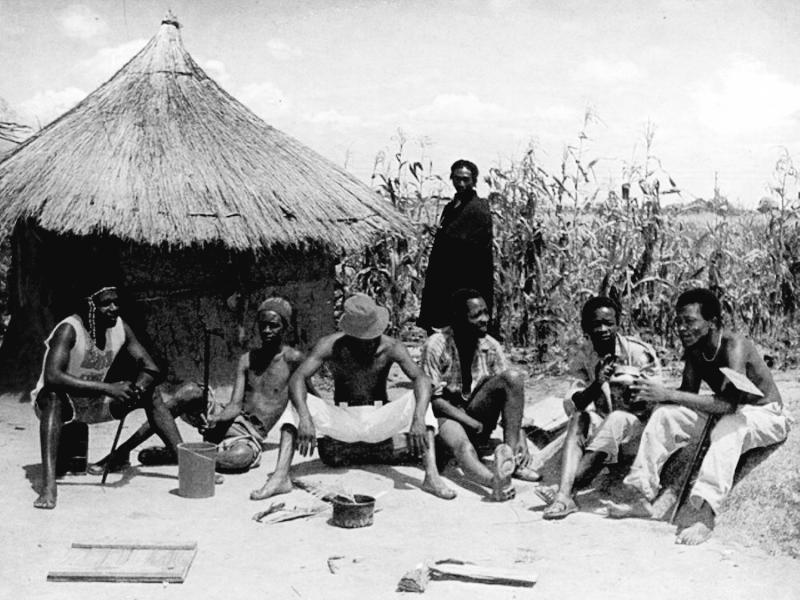

The late Cont Mhlanga

“It’s partly why I left the industry,” Majaivana reveals. “You might say my music was not better than theirs but after travelling a lot in places like Sweden, England, Denmark and Canada, we had full houses and at home here it was on tribal lines,” Majaivana explains, refusing to commit an optimistic take on the future. As the late Cont Mhlanga said, it’s pointless to petition Majaivana to come home – there have been several petitions over the years – when the best musicians from Matabeleland still look outside Zimbabwe for support. Besides, while lesser contemporaries have been carefully curated, only two studio albums by Majaivana are available in CD or digital format, and the rest of his work is well on its way to be lost.

Totem gaze

A totem is an origin story. The totem animal, an avatar with a life of its own, walks through the unity of life shared by the individual with the natural environment, which the animal represents, and the civilisational weave, which the ancestors represent. In totem poems, the mythic, the majestic and the mundane in the life of a people is dissolved into the spiritual content of their bloodline. We have already seen that the fate of totems is to be tamed just as the fate of tradition is to become missionary language. Official tradition, however, creates its own dissociative outside.

Not without vulgar racism, Western metaphysics can be read as claiming for totem culture a subversive opposition to the dominant social order. In the Darwinian tradition, animals represent the childhood of humankind. In the Freudian tradition, childhood trauma forces its return when an individual struggles with the demands of civilisation. From here, it’s one step for Freud to claim parallels between psychological disorder and “primitive” totem culture.

Hegel’s blackface dialectic claims childlike parallels between animals and Africans. The shared naivety he sees in them just as easily switches to monstrosity and madness. For Slavoj Zizek, the withdrawal from the world that constitutes madness for Hegel is an opening for freedom, just as Descartes passes through madness to consciousness in his founding gesture of humanisation.

In Jacques Lacan’s mirror stage, identification happens when a child first recognises itself in a mirror image exterior to itself. In Jacques Derrida’s late meditations in posthumanism, identification happens when the animal stares back at the human, while Dambudzo Marechera and Georgio Agamben’s human creates himself by differentiating himself from the animal in the mirror.

The animal in Marechera’s mirror treasures a cosmic joke at its human viewer’s expense. “Burning in the Rain” ends with a smashed mirror but its shards are just dissociative splinter totems that will populate the next stories. As Marechera’s primal encounters extend to dogs, cats, warthogs and menfish in The House of Hunger short stories, he has to defend himself with all the civilisational filters at his disposal, from clothes to attitudes and books.

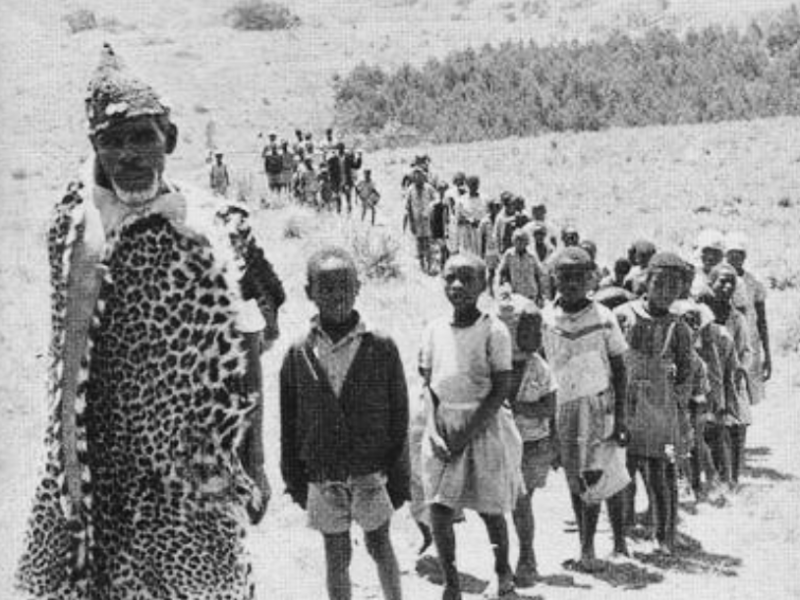

“The underwear of our souls was full of holes…we were whores, eaten to the core by the syphilis of the white-man’s coming.” – Dambudzo Marechera, ‘House of Hunger’. Photo: Ernst Schade

“There is something in every animal which is also in us and, I felt, to know it too closely was to court the disaster of a morbid fascination which only the devil knows,” Marechera observes. Bewildered by the weirdly human translucence of a cat’s gaze, Marechera sends English hardbacks raining on it, “a complete Shakespeare, a complete Oscar Wilde, the Variorum edition of Yeats’ plays, a Concise Oxford Dictionary, and Thomas Hardy’s Collected Poems,” as if white culture is the antidote to the animal in all men.

Majaivana with Freud

In Freud’s othering register, “savage customs” provide insight into psychoanalysis, the “science” he invented to explain human behaviour. His famous book, Totem and Taboo, explains the relationship between totems and the unconscious. Neither the claims of science nor the demands of civilisation diminish the spiritual power of totems. They drive them just where Freud wants them: the unconscious.

Forgotten childhood experiences provide the hidden content that will displace itself to adult conflicts. The unconscious, a loose network of fear, guilt, repression, amnesia, compulsion, enjoyment, displacement, prohibition and other drives, conditions a person’s behaviour without being visible to her. Its symptoms hide in plain sight, in everyday language, as slips of tongue and wordplay, and in dreams.

Freud traces totem culture back to the childhood of humankind, just as he has already traced the unconscious back to identity-forming childhood experiences. In leaning into rawer orature, Majaivana concurs with Freud’s gesture. Earlier than any other Zimbabwean musician, he confronted the new nation’s neurosis using folk images that have been edited out of the patriotic songbook. We break down individual songs in the next of this two-feature series.

Leave a Reply