| Dominic Benhura (Photo: Shona Art) |

Book: Mawonero/Umbono

Edited by Ignatius Mabasa

Publisher: Kerber Verlag (2015)

ISBN: 978-3-86678-937-1

Zimbabwe’s earliest patriarchs were masters of art. The keynote symbols of our national identity are drawn from their visual heritage.

San rock art prefaces the compendium of local history, while the Zimbabwe Bird, a soapstone legend of the Hungwe people, is the national emblem.

Visuals arts are at the head of our cultural strivings, in the pixels of our national identity, across the tapestry of history and at the centre of a dynamic creative industry.

Zimbabwe’s daring strokes on the world mural have been sustained by contemporary masters, Dominic Benhura, Tapfuma Gutsa, Chikonzero Chazunguza and others, while recent appearances such Calvin Chimutuwah are exploring novel tangents.

These cross-currents of the Zimbabwean tradition are discussed in a newly released book “Mawonero/Umbono: Insights on Art in Zimbabwe.”

“Mawonero” is Shona for “perspective,” while “umbono” is the Ndebele equivalent. Insider perspectives on Zimbabwean art by Raphael Chikukwa, Doreen Sibanda, Zvikomborero Mandangu, Tashinga Matindike-Gondo and Farai Chabata make up the new publication.

While there has been no shortage of material on Zimbabwe’s visual arts sector, the contributors attempt an exclusively Zimbabwean joint feat and generously upload representative artworks into their narrative.

The five artists and curators take us to the gallery to meet the varied maze of prodigies, clairvoyants, nationalists, missionaries, introverts, entrepreneurs, rebels and perverts who have contributed to the canon of local art.

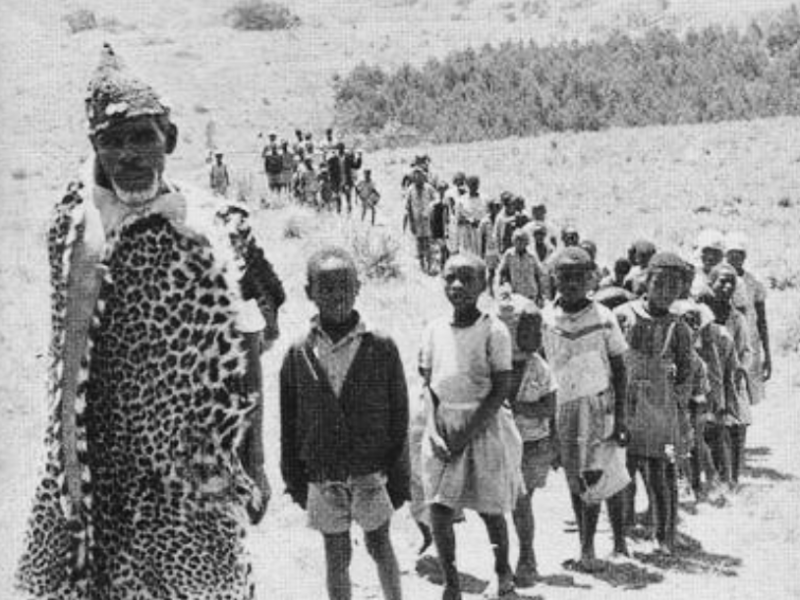

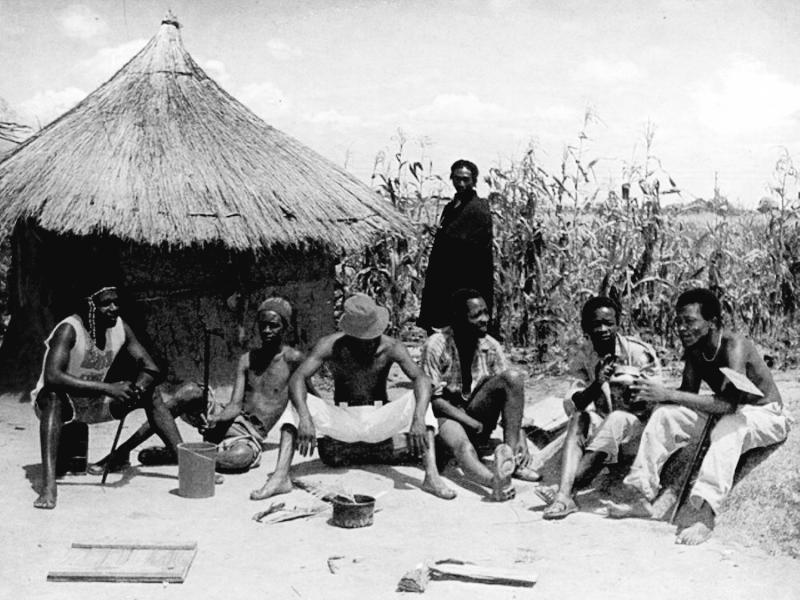

The book sets out with the mid-century missionary and secular interventions of the 1950s, with particular emphasis on Serima Mission, Cyrene Mission, Mzilikazi Arts and Craft Centre, the National Gallery and the Tengenenge Art Centre, and runs the thread to the present.

National Gallery of Zimbabwe executive director Doreen Sibanda and Zimbabwe German Society cultural interventions advisor Roberta Wagner argue the case for a locally generated work as a means to counter commercially motivated foreign texts on Zimbabwean art.

The opening article, authored by National Gallery of Zimbabwe chief curator Raphael Chikukwa, is titled “Returning to the Early Conversations: Re-Examining Missionary and Non-Missionary Interventions in the Development of Art in Zimbabwe.”

The article is informative as it ushers the reader decades back to not so much the beginning, as patronising narratives have alleged, but rather the formalisation of Zimbabwe’s visual arts in the 1950s.

The interventions, chiefly attributed to Canon Ned Paterson of Cyrene Mission, Father Hans Groeber of Serima Mission, Frank McEwen of the National Gallery and Tom Blomefield of Tengenenge Arts Centre, harnessed local talent into an agency for industrial-strength products.

Chikukwa begins by chanting down the mono-sourced characterisation of Zimbabwean art as a by-product of the colonial establishment.

He emphasises that the urge to create antedates Rhodesian institutions, a claim sufficiently corroborated by the creative wealth of the Great Zimbabwe and the millennia-old rock paintings of Matobo Hills.

“Arguably, in the eyes of Western scholars, Paterson of Cyrene, Groeber of Serima, McEwen of the National Gallery and Bloemefield of Tengenenge are synonymous with the birth of Zimbabwean art,” observes Chikukwa.

“They are erroneously believed to be the godfathers of the country’s art movement. It is important to note that every generation keeps on interrogating its past and that the rewriting of history is a continuing process.

The claim that colonial masters introduced art to Zimbabwe is foiled in light of creative expressions such as painting, music, dance, folklore, poetry and sculpture which constituted the alphabet of indigenous culture prior to colonisation.

He acknowledges, and devotes a generous segment to, the contributions of colonial institutions to Zimbabwe’s visual arts but argues the case for locating the native foundation.

Paterson and Groeber, who were both art enthusiasts in addition to being missionaries, trained art at their mission schools primarily as an evangelical medium but also as a chronicle of the native experience.

The institutions facilitated the emergence of early notables Sam Sango, Lazarus Khumalo, Nicholas Mukomberanwa, Gabriel Hatugari, Ernest Bere and exposed the young Africans’ works to the international market.

Big fans included Queen Elizabeth who visited Cyrene Mission and obtained artworks which are said to be at the Birmingham Palace to this day.

McEwen, Blomefield and Paterson are rapped for encouraging a market-informed tendency whereby artworks were romanticised to suit the European idea of an exotic African culture.

He also brings up the manipulation of Zimbabwean artists who were paid paltry fractions of what their work fetched on the international market and, in some cases not paid at all.

Sibanda’s article “Main Drivers for the Growth and Development of Sculpture Movements in Zimbabwe” also faults the early interventionists for the homogenous and commercialised tendency of early Zimbabwean sculpture.

Her contribution revolves around the same period, with particular emphasis Tengenenge and the National Gallery, formed in 1956 as the Rhodes National Gallery, and its extensions, the Workshop School and the International Congress of African Culture.

African notables from the period include Henry Munyaradzi, Ben Matemera, Kingsley Sambo, Thomas Mukarobgwa and Charles Fernando.

Sibanda reconstructs the Stone Movement beginning 1980s which broke away from the foregoing to explore trending political and social phenomena.

Imaginatively potent exponents of the era include cousins Gutsa and Benhura, who are still legends in the game, Eddie Masaya, the Madamombes and others.

Sibanda laments the regress of the arena, thanks to charlatans, overproduction and lack of originality.

Mandangu, an artist and adminstrator at the National Gallery makes the connection from the directed tradition of the 1950s to the present in an article titled “Bridging the Contemporary.”

He credits Marshal Baron of Bulawayo as one of the first local artists to incorporate expressive and emotional features into his workflow.

The contemporary begins in earnest in the late 1970s as artists process decolonisation and the promise of Independence, thereby definitively breaking away with their politically agnostic predecessors.

“From Baron to the present day, art has served as a time capsule which offers a window to the spirit of different eras,” observes Mandangu.

Matindike-Gondo, an artist and academic, provided historical snapshots of the period 1989 to 1999 in her article “The Politics of Art – Art Education and Culture in the Nineties.”

She walks us through the economically turbulent 1990s and reconstructs artists’ response to austerity and uncertainty of the decade.

Matindike-Gondo credits exponents of the era for diversifying the Zimbabwean tradition, hitherto dominated by sculpture, to champion other media.

Chabata, a senior curator of Ethnography at the Zimbabwe Museum of Human Sciences, deals with “Changing Contexts for the Growth of Zimbabwean Contemporary Art.”

Chabata locates the beginning of contemporary art in the mid-1980s, and at the advent of mixed media and experimental tangents.

His tribute offers homage to touches of genius in the arena of the day, notably Masimba Hwati and my personal favourite Calvin Chimutuwah, who has ventured into an exciting experiment with natural paints.

“I can hardly live without expressing my love, respect and view of nature from my heart through the paint brush and the canvas,” Chimutuwah says in an interview with Chabata.

“The satisfaction of making someone wander through art is more rewarding than financial gain. I believe creativity is a phenomenon which makes this world a better place, and more enjoyable,” he says.

In the last word, “Framing the Contemporary,” Sibanda acknowledges the cross-pollination of local art with cosmopolitan influences and credits the resilience of the Zimbabwean tradition in the absence of high level infrastructure.

Leave a Reply